In an increasingly interconnected world, both investors and governments seek new strategies to navigate global opportunities, and Investment Migration is one of them. According to the Investment Migration Council((Investment Migration Council. What Is Investment Migration? Investment Migration Council, 2025. Retrieved from https://investmentmigration.org/about/what-is-investment-migration/)) “Investment migration is a form of legal migration used by over 80 countries. It includes Citizenship and Residence-by-investment programs that grant status in return for investment. These programs are often built around entrepreneurship potential, a long-standing feature of immigration policy in many OECD states.”

From a single program in 1982 to 89 programs worldwide, the industry has continued to evolve and introduce new approaches.

The opportunities granted by the Investment Migration sector reflect the intersection of migration policy, international investment, and national development strategies. The motivations are twofold: for investors, such programs offer enhanced mobility, security, and access to global markets; for states, they provide avenues for foreign direct investment (FDI), fiscal revenues, and economic diversification.

This briefing examines the Investment Migration Industry through the lens of its history, evolution, typologies, and the major developments it has undergone. It also explores the current landscape of investment migration by focusing on 113 CBI, RBI, and Entrepreneur Visas, analyzing their regional distribution and presenting the most up-to-date data on investment migration programs by comparing and contrasting affordability, prestige, and prevailing nationalities.

To understand the investment migration landscape today, it is essential to look back at how these programs emerged and evolved, providing valuable context for their overall development.

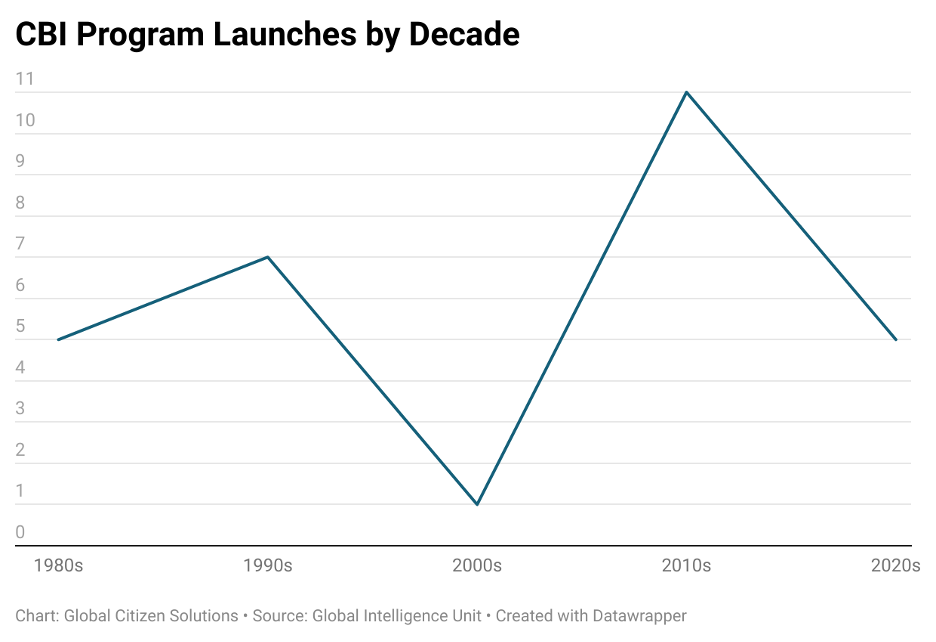

Citizenship by Investment: The first program started in 1982 in Tonga. Soon after this, St. Kitts and Nevis launched its citizenship-by-investment program in 1984, just one year after gaining independence. Today, it stands as the world’s longest-running program and continues to set the benchmark for Citizenship by Investment initiatives((“St. Kitts and Nevis Tops 2024 CBI Index as Best Citizenship by Investment Programme.” Gulf News, 2024. Retrieved from https://gulfnews.com/business/corporate-news/st-kitts-and-nevis-tops-2024-cbi-index-as-best-citizenship-by-investment-programme-1.1728395225354)). From there, other countries quickly joined the trend, with Belize in 1985, the Marshall Islands in 1987, Ireland in 1988, and Caribbean nations such as Dominica and Grenada stepping in during the early 1990s. The 2010s is the most active decade to date, with 11 programs including Cyprus, Malta, Vanuatu, Turkey, and others. The 2020s continue the trend with five new programs so far (Egypt, North Macedonia, El Salvador, Nauru, Botswana), underscoring the continued global relevance of investment migration.

Figure 1. Inception of CBI Programs Grouped by Decade

The rise and current concentration of CBI programs in the Caribbean was driven by a mix of mounting challenges: declining foreign aid and investment, the global aftershocks of the 2008 financial crisis, and a series of natural disasters that placed heavy pressure on GDP. In response, Caribbean nations began seeking innovative economic tools, paving the way for early citizenship-by-investment initiatives((Surak, Kristin. “Global Citizenship 2.0: The Growth of Citizenship by Investment Programs.” IMC-RP 2016/3, Investment Migration Council, 2016, Retrieved from https://investmentmigration.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Surak-IMC-RP3-2016.pdf.)).

Residence by Investment: RBI programs, commonly known as Golden Visas, emerged in the 2010s, particularly across Southern Europe during and after the Eurozone financial crisis. Countries such as Portugal, Greece, and Spain introduced RBI schemes as a strategic means of attracting capital inflows, strengthening real estate markets, and stimulating foreign investment, without increasing immigration in the conventional sense((Global Citizen Solutions. Global Residency and Citizenship by Investment Report. 2025. Retrieved from https://www.globalcitizensolutions.com/report/global-residency-and-citizenship-by-investment-report)).

The modern “Golden Visa” model is often traced to Bulgaria’s residence-by-investment program introduced in 2009, followed by Latvia’s 2010 launch of a property-linked residence pathway. This wave continued shortly thereafter with Portugal in 2012, and Greece, Spain, and Cyprus in 2013.

Entrepreneur Visas: The evolution of entrepreneur investor categories began with Canada’s Immigrant Investor Program in 1986((Surak, Kristin. The Economics of Investment Migration: The Citizenship and Residence Industry and Economic Outcomes. Working Paper no. 158, The Centre on Migration, Policy & Society (COMPAS), University of Oxford, June 2022. Retrieved from https://www.compas.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/WP-2022-158-The-Economics-of-Investment-Migration-The-Citizenship-and-Residence-Industry.pdf)). Unlike later passive investment models, this program centered on human capital, requiring applicants to demonstrate business expertise, entrepreneurial activity, or direct management of their investments. The United States followed with the EB-5 Immigrant Investor Visa in 1990, and the United Kingdom introduced a similar investor migration route in 1994, marking the early development of what would become a broader landscape of active investment-driven migration options. It should be noted that this briefing treats these visas as active investor routes, although some frameworks also classify them under the broader residence-by-investment category.

Program design in investment migration has not been linear: alongside new launches, several high-profile programs closed or altered as governments reassessed their fit with policy priorities and risk controls. Ireland, for example, closed its Immigrant Investor Program (IIP) to new applications from 15 February 2023, noting it had been introduced in 2012 during a period when the economy needed investment and stating that, in changed circumstances, such investment routes were no longer needed((Irish Immigration Service. Immigrant Investor Programme (IIP): Updated FAQs. January 2024. Retrieved from https://www.irishimmigration.ie/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/IIP-UpdatedFAQ-Final.pdf.)).

Other notable developments followed with Spain announcing it would end the issuance of investor residence permits, particularly those tied to real-estate purchases over €500,000, effectively abolishing “Golden Visas” for investors as of 3 April((Gobierno de España. “El Gobierno pondrá fin a las ‘Golden Visa’ vinculadas a inversiones inmobiliarias.” La Moncloa, 2025, Retrieved from https://www.lamoncloa.gob.es/serviciosdeprensa/notasprensa/vivienda-agenda-urbana/Paginas/2025/020425-fin-golden-visa.aspx)). Cyprus likewise moved to abolish its CBI program in response to reported abuses and long-standing weaknesses in its design and oversight((Pegg, David. “Cyprus Scraps ‘Golden Passport’ Scheme after Politicians Caught in Undercover Sting.” The Guardian, 2020, Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/oct/13/cyprus-scraps-golden-passport-scheme-after-politicians-caught-in-undercover-sting)). At EU level, an ECJ decision marked a further inflection point, with Malta’s Exceptional Investor Naturalization (MEIN) program effectively reaching the end of its legal road((“The ECJ Has Spoken: A Turning Point for Malta’s Exceptional Investor Naturalisation (MEIN) Program.” Global Citizen Solutions, Retrieved from https://www.globalcitizensolutions.com/the-ecj-has-spoken-a-turning-point-for-maltas-exceptional-investor-naturalisation-mein-program/)).

At the same time, other jurisdictions have responded through program redesign rather than full termination – for instance, Portugal’s “More Housing” law((Diário da República Eletrónico. “Lei n.º 56/2023.” Retrieved from https://diariodarepublica.pt/dr/detalhe/lei/56-2023-222477692.)) (Law No. 56/2023 of 6 October 2023) changed its Golden Visa framework by eliminating the real estate investment route, reflecting how governments may adjust qualifying investments to address domestic policy priorities while maintaining alternative pathways.

Another development that should be noted is that advanced economies have been reconsidering their residence-by-investment strategies to attract talent and capital. Examples include the Gold Card launched by the United States((Economic Times. “US Moves Closer to Launching Trump’s Gold Card for Permanent Residency.” The Economic Times,2025, Retrieved from https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/nri/migrate/us-moves-closer-to-launching-trumps-gold-card-for-permanent-residency/articleshow/125458617.cms. )); New Zealand’s revision of its Active Investor Plus program((Immigration New Zealand. “Investor Category.” Immigration New Zealand, Retrieved from https://www.immigration.govt.nz/about-us/news-centre/investor-category/.)), which simplified the route and reported a marked increase in applications under the new framework; and UK discussions, reported by Bloomberg((Bloomberg News. “UK Said to Consider New Investor Visa Targeting Key Sectors.” Bloomberg, May 2025, Retrieved from https://www.bloomberg.com/news/newsletters/2025-05-15/uk-said-to-consider-new-investor-visa-targeting-key-sectors.)), on a potential new investor visa targeted at funding “strategic” sectors such as AI, clean energy, and life sciences – signaling a possible pivot from broad passive investment toward more policy-directed capital attraction.

Currently, the investment migration industry has become a dynamic global framework through which countries compete for investment, innovation, and talent. Over time, these programs have expanded in purpose, design, and regional reach.

As explained above, investment migration visas can be classified into two main categories: Citizenship by Investment and Residence by Investment, and a broader category: Entrepreneur Visas.

Across the global mobility landscape analyzed in this briefing, RBI programs form the clear majority, accounting for around 64% of all active pathways. CBI programs represent about 14%, reflecting their presence in a relatively small group of jurisdictions, while Entrepreneur Visas comprise roughly 22%, emerging as a steadily expanding category that bridges residency and entrepreneurship.

01/ Citizenship by Investment (CBI)

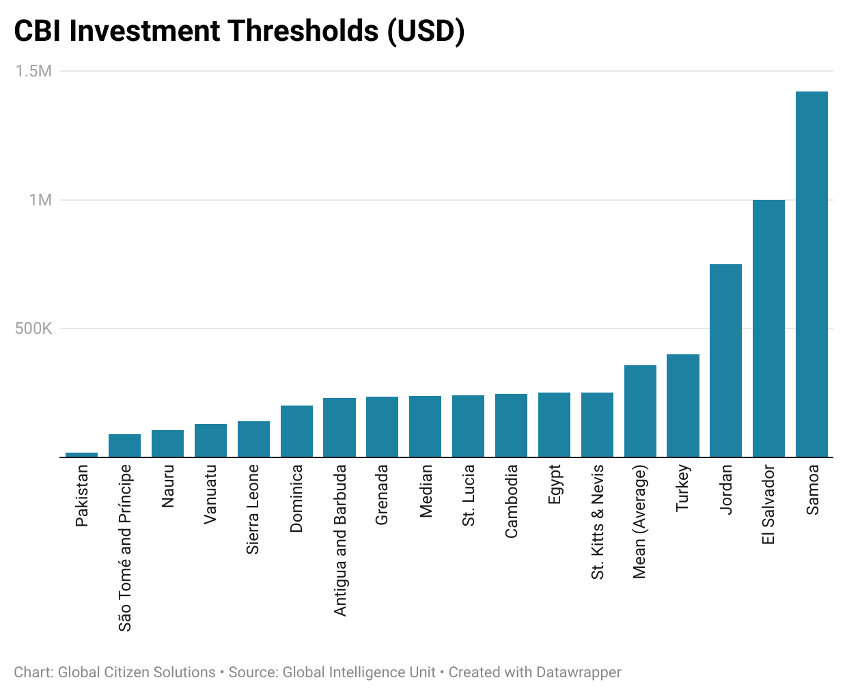

Globally, citizenship-by-investment programs are becoming increasingly diverse, with 16 active options across the Caribbean, the Middle East, Africa, Asia, and Oceania. Investment thresholds vary widely: the median minimum investment is $242,500, while the average is around $324,000.

Figure 2. Minimum Investment Amounts of CBI Programs

Caribbean programs remain in a steady mid-range. While, on the lower end of the spectrum, countries like Nauru ($105,000) and Pakistan ($18,000) provide low-cost pathways. At the premium end, Samoa and El Salvador now exceed the $1 million mark, representing the high-capital tier. Overall, this spread shows how the global CBI market is evolving to meet a wide range of investor budgets, motivations, and priorities.

Furthermore, new programs are being launched geographically, extending the market into additional regions. Examples include Argentina and Botswana, with proposed investment levels of $500,000 and $75,000, respectively – an option expected to appeal to investors seeking more accessible and affordable pathways as emerging CBI markets develop.

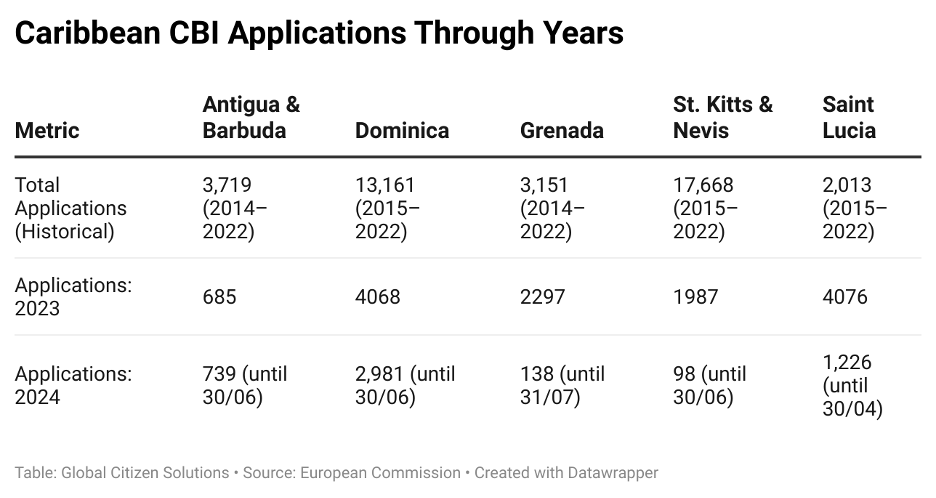

Figure 3. CBI Countries’ Data Provided to the European Commission

The tables above present the latest figures submitted to the European Commission((European Commission. Seventh Report under the Visa Suspension Mechanism, COM (2024) 571 final. 6 Dec. 2024. Retrieved from https://www.imidaily.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/COM_2024_571_FIN_EN_TXT.pdf)) by the Caribbean states operating Citizenship by Investment (CBI) programs. Overall, the data shows a consistent upward trend in approved applications across most jurisdictions, while rejection rates remain comparatively low.

Nationalities applying for CBI: When looking at the nationalities driving demand for CBI programs, the available data points to distinct patterns across jurisdictions. In Grenada, the most recent 2025 figures((IMA Grenada. IMA Grenada Quarterly Statistics: Q2 2025. 2025. Retrieved from https://imagrenada.gd/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/KNVS-IMAGR-00036-IMA-Q2-Statistic-Report-v2.pdf)) show that Chinese nationals are the largest applicant group, representing 13% of all submissions. Antigua and Barbuda’s data, while from 2023, reveals a different trajectory: in the program’s first four years((IMI Daily. “First Data Batch in 3 Years Reveals Antigua & Barbuda CIP Now Caribbean’s Least Popular Program.” IMI Daily, 18 July 2023. Retrieved from https://www.imidaily.com/caribbean/first-data-batch-in-3-years-reveals-antigua-barbuda-cip-now-caribbeans-least-popular-program/.)), around 40% of applicants were Chinese, but over the last five years that share has fallen to about 15%. During the same period, interest from Nigerian investors has surged – since the first half of 2020, Nigerians have consistently been the program’s single largest applicant group.

02/ Residency by Investment (RBI)

Real estate has long been the primary investment route in residence by investment programs, especially in the Mediterranean, but many countries now offer a broader set of options, including business creation, private-equity or venture-capital funds, government bonds, bank deposits, and contributions to national development funds. This shift reflects efforts to balance economic impact, regulatory oversight, and investor demand while directing investment toward more targeted national priorities((Global Citizen Solutions. Global Residency and Citizenship by Investment Report: Full Report. 2025. Retrieved from https://www.globalcitizensolutions.com/report/global-residency-and-citizenship-by-investment-report-full-report/#footnote_11_7012)).

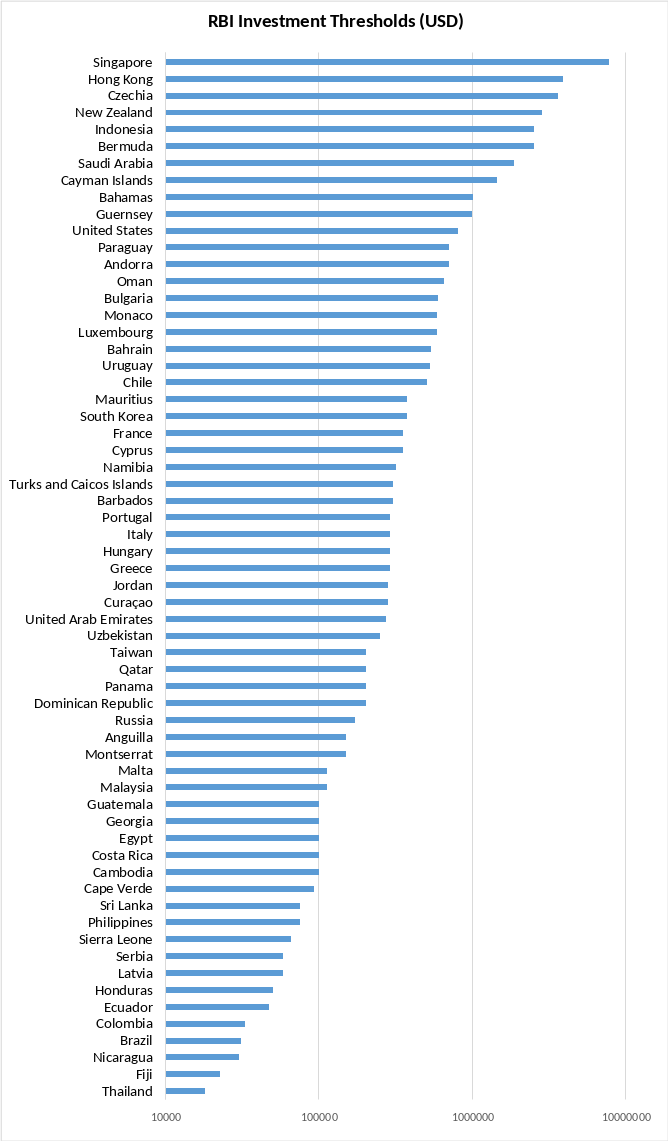

Based on our data, there are a total of 72 countries operating residence-by-investment (RBI) programs. While most jurisdictions specify a clear minimum investment threshold, others such as Albania, Armenia, and Venezuela employ differing or less formalized practices, which is why they are not represented in the visualization below.

Figure 4. Minimum Investment Amounts of RBI Programs

Residence-by-investment programs display a wide range of minimum capital requirements, though most fall between $100,000 and $400,000, with a median of around $230,000 based on the analyzed data. A small cluster of jurisdictions offers lower investment thresholds- from $18,000 in Thailand to $31,000 in Brazil- making these programs particularly attractive to cost-sensitive applicants seeking straightforward relocation routes. The mid-range segment, which represents the largest share of available options, includes countries such as Costa Rica, Georgia, Panama, and Mauritius. These destinations tend to draw practical investors looking for stability, lifestyle benefits, and regional mobility without the need for substantial capital commitments.

At the higher end of the market, jurisdictions such as Singapore, Hong Kong, the Cayman Islands, and Saudi Arabia set requirements between $1 million and over $7 million. These programs generally target high-net-worth individuals whose priorities include wealth protection, robust financial systems, and global prestige. Meanwhile, several European options – particularly those in Portugal, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Luxembourg, and Monaco- cluster around €250,000 to €500,000, positioning themselves as strong choices for investors seeking quality of life, safety, education, and long-term integration rather than purely financial optimization.

The RBI landscape continues to diversify shaped by geopolitical dynamics and investor mobility trends. Collectively, these shifts illustrate an increasingly adaptive RBI market, offering everything from low-cost mobility pathways to premium residency routes in highly developed, globally connected jurisdictions.

Nationalities applying for RBI: Demand for residency-by-investment programs is shaped by a diverse mix of nationalities across regions.

In April 2023, Portugal’s immigration authority issued 116 ARI residence permits under the country’s investment migration framework. According to the Portuguese Immigration and Border Service((Portuguese Immigration and Borders Service. ARI – April 2023. 2023. Retrieved from https://www.sef.pt/en/Documents/ABRIL_2023%20ARI.pdf)), the United States accounted for the largest share of new investors with 28 approvals, followed by China with 15 and the United Kingdom with 14. South Africa and Lebanon each recorded 7 approvals, rounding out the leading nationalities for that month.

Similarly, the U.S. Department of State’s Report of the Visa Office 2023((U.S. Department of State. Table V (Part 3): Immigrant Visas Issued and Adjustments of Status Subject to Numerical Limitations, Fiscal Year 2023. 2024. Retrieved from https://travel.state.gov/content/dam/visas/Statistics/AnnualReports/FY2023AnnualReport/FY2023_AR_TableV_Part3.pdf)) reveals that mainland China alone accounted for 6,262 EB-5 visas in FY2023, with India (815), Vietnam (556), South Korea (446), and Taiwan (261) making up the rest of the leading group. Together, these numbers highlight Asia as the dominant source region for investor migrants entering the United States through the EB-5 program.

As for Greek Golden Visa, in 2023 Chinese nationals remain the largest group of Greek Golden Visa holders (with 58%), followed by investors from Turkey (7%)((IMI Daily. “Greek Golden Visa Was the World’s Most Popular in 2023; Time to Abolish the Program, Says Main Opposition Party.” IMI Daily, 2024. Retrieved from https://www.imidaily.com/europe/greek-golden-visa-was-the-worlds-most-popular-in-2023-time-to-abolish-the-program-says-main-opposition-party/.)).

Across these programs, the rising share of applicants from advanced economies such as the United States and the United Kingdom, particularly visible in Portugal, signals a shift away from a capital-driven migration toward lifestyle, mobility, and long-term quality-of-life motivations.

03/ Entrepreneur Visas

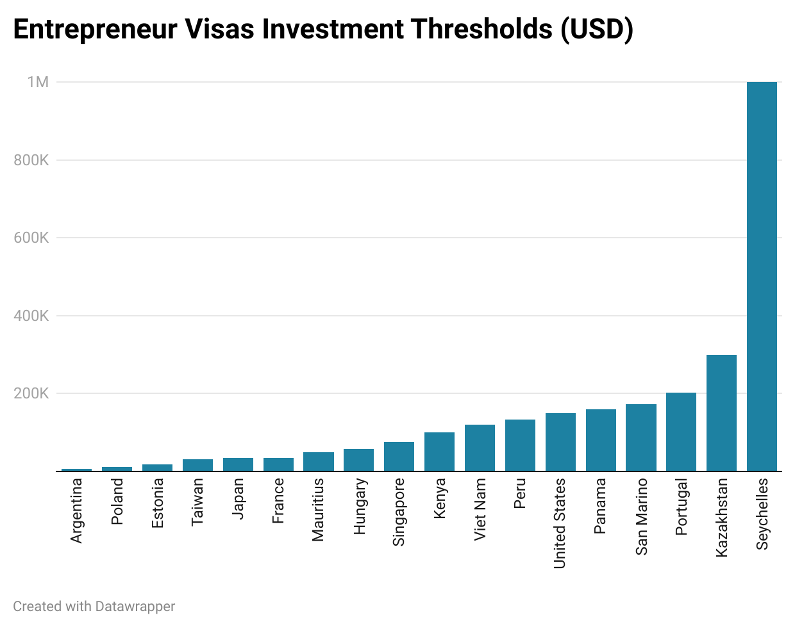

As a broader category, Entrepreneur Visas landscape looks as follows:

Figure 5. Minimum Investment Amounts of Entrepreneur Visa Programs

The total number of investor programs analyzed is 25. The Investor-visa programs vary widely in cost, with Argentina (Inversionista) ($7,000), Poland (€12,000), and Estonia (€16,000) offering some of the most affordable options, while Seychelles ($1,000,000), New Zealand ($565,630), and Kazakhstan ($300,000) are at the upper end of the spectrum. Mid-range options such as Hungary (€50,000), Panama ($160,000), and Portugal (€175,000) provide a balance between accessibility and competitiveness. Several countries, including Canada, the United Kingdom, Italy, and Israel, offer investor pathways without a formally required minimum, emphasizing business creation and economic contribution over fixed capital injections. The categories with no fixed investments were left out of the visualization presented above.

To sum up, across the three categories, CBI programs are overwhelmingly concentrated in small island economies – around 75% of all CBI jurisdictions – reflecting the reality that investment migration is fiscally significant((International Monetary Fund. Macroeconomic Developments and Prospects in Low-Income Countries — 2025. Policy Papers, Issue 008, 22 Apr. 2025. Retrieved from https://www.elibrary.imf.org/view/journals/001/2025/008/article-A001-en.xml)) for small states((Surak, Kristin. The Economics of Investment Migration: The Citizenship and Residence Industry and Economic Outcomes. Working Paper No. 158, Centre on Migration, Policy & Society (COMPAS), University of Oxford, June 2022. Retrieved from https://www.compas.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/WP-2022-158-The-Economics-of-Investment-Migration-The-Citizenship-and-Residence-Industry.pdf)). RBI programs, while strongly represented in high-income economies that leverage residence rights, lifestyle advantages, and regulatory stability, also appear widely across middle-income countries, demonstrating that RBI is not exclusively a tool of advanced economies. Entrepreneur Visas, meanwhile, form a genuinely intermediate category: their thresholds span low-, middle-, and high-income jurisdictions, and their design emphasizes entrepreneurship and targeted economic participation rather than passive capital inflows.

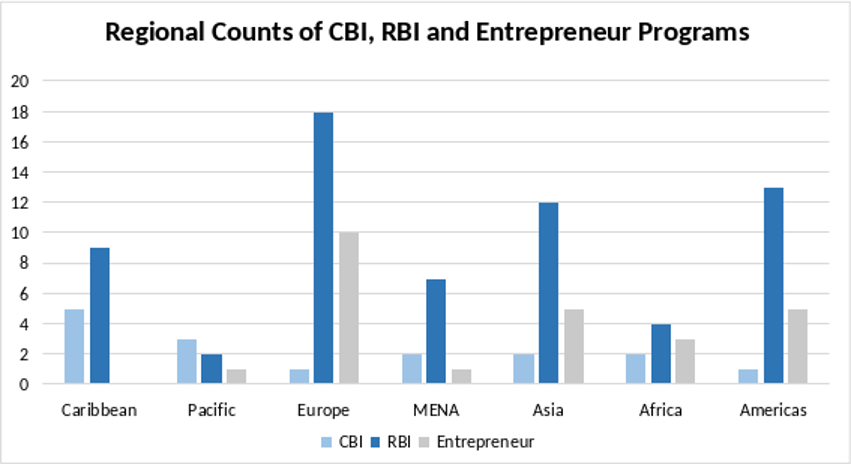

Looking at the regional variations of investment-migration programs, clear geographic patterns emerge across the three categories. CBI programs overwhelmingly dominate in the Caribbean and Pacific microstates, where small island economies rely on direct fiscal inflows as a core revenue strategy. RBI schemes are most prevalent in Europe, the Middle East, and parts of East Asia, regions where higher-income jurisdictions leverage residence rights, regulatory stability, and lifestyle advantages to attract long-term capital. Entrepreneur Visas show a far more dispersed regional footprint, appearing across Latin America, Eastern Europe, Africa, and high-income OECD countries alike – reflecting their flexible design and suitability for economies seeking to channel investment into entrepreneurship, innovation, and targeted development priorities.

Figure 5. Regional Representation of Investment Migration Programs

The chart shows clear differences in how widely each program type is adopted across regions. Europe and the Americas have the highest overall number of programs, reflecting their larger number of participating countries and more established policy infrastructures. Asia also has a substantial presence, particularly in RBI and Entrepreneur models. By contrast, Africa, MENA, and the Pacific feature fewer programs in absolute terms, indicating smaller or more selective adoption of investment-migration pathways. Overall, the distribution highlights how regional program density is shaped as much by the number of countries in each region as by their policy preferences.

The chart also counts North Macedonia as a CBI program in Europe, but it should be noted that publicly verifiable official documentation and successful-case transparency are limited. Thus, it is included here only as ‘reported’ rather than confirmed operational.

However, the industry is changing rapidly, and the MENA region is actively expanding its investor-residence and “golden visa” programs as part of economic diversification strategies away from oil dependence, examples are Saudi Arabia((Global Citizen Solutions. Saudi Arabia: From Oil Reliance to a Diversified Investment Hub. Global Citizen Solutions, 2025. Retrieved from https://www.globalcitizensolutions.com/saudi-arabia-investment-hub/)), Oman, Kuwait etc.

As for the regional comparison of average thresholds, Africa and Asia host the most affordable programs, reflecting their emphasis on accessibility and capital attraction. In contrast, Europe, MENA, and parts of the Pacific feature more premium programs, where higher minimums align with stronger regulatory systems and higher-value investment routes.

Recent transformations in Investment Migration programs show a decisive shift from simple and transactional routes toward more structured, purpose-driven investment mechanisms. In both CBI and RBI strategies, governments increasingly deploy government-approved funds, development bonds, sustainability-linked vehicles, and sector-targeted platforms to channel foreign capital into national priorities such as climate resilience, urban renewal, tourism development, and post-disaster recovery. This reflects a rise in mission-driven investment options.

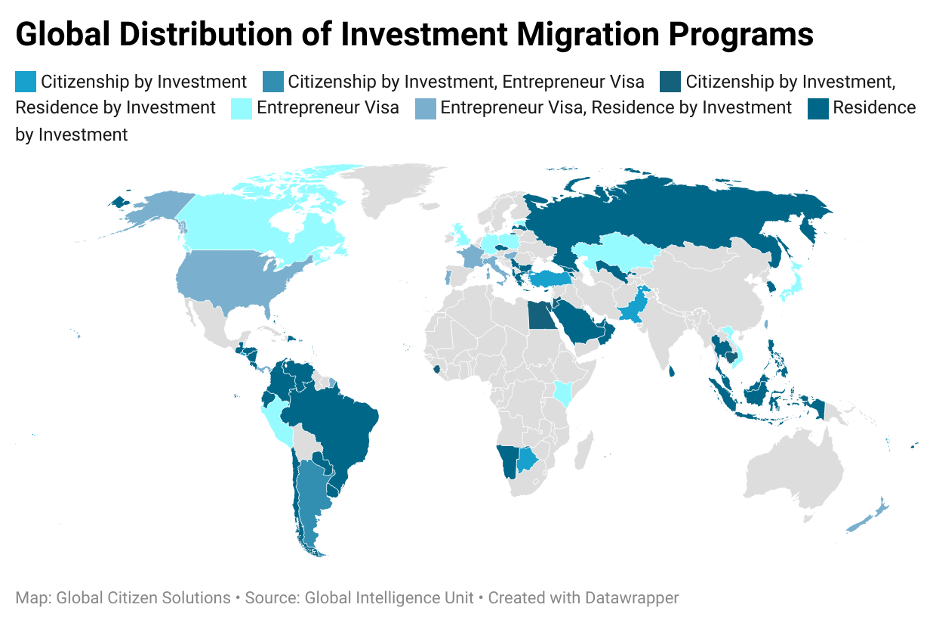

Figure 6. Map of Countries Operating IM Programs

Another notable change is personalization. Unlike early CBI models that offered a single, straightforward donation route, modern programs allow highly customizable investment types making it possible for each investor to select a program that reflects their financial profile, values, and long-term objectives.

A further strategic transformation lies in the modernization of program administration, marked by the rapid digitalization of application processes, the adoption of e-KYC tools((Investment Migration Council. “Onboarding Prospective Applicants: Raising the Bar with Enhanced KYC.” Investment Migration Council, 2025. Retrieved from https://investmentmigration.org/articles/onboarding-prospective-applicants-raising-the-bar-with-enhanced-kyc/ )), and the integration of biometric and data-driven risk-management systems.

Parallel to this shift is the increasing sophistication of due-diligence practices, as governments employ multilayered background checks, ongoing monitoring procedures, enhanced international cooperation, and specialized risk-assessment providers.

Complementing these developments is a growing emphasis on transparency and public accountability, with many states releasing audited reports, detailed revenue breakdowns, and registries of approved investment vehicles. Together, these changes reflect an industry moving toward greater efficiency, regulatory maturity, and institutional credibility.

Policy Recommendation: Programs should continue integrating investment routes into long-term development strategies, broadening sustainable and socially impactful options, upholding strong governance and due-diligence standards, and diversifying investment vehicles so that investment migration can support national objectives while meeting investor expectations.

Direct donations to the government provide a clear mechanism for directing funds toward priority areas((https://www.compas.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/WP-2022-158-The-Economics-of-Investment-Migration-The-Citizenship-and-Residence-Industry.pdf )). Portugal is a great example that this can transform specific sectors by channeling investor capital into cultural initiatives, heritage restoration, and urban revitalization((https://www.globalcitizensolutions.com/cultural-investment-pathway-for-the-golden-visa-in-portugal/ )).

This briefing sought to examine the investment migration industry from a typological perspective, tracing its origins, structural evolution, and emerging strategic shifts. By presenting a unified analysis of 113 programs, including Citizenship by Investment, Residence by Investment, and Entrepreneur Visas, it offers a rare, comprehensive overview. The findings indicate that Residence by Investment programs dominate the global landscape, shaping both market dynamics and policy design.

Clear geographic patterns further illuminate the industry’s structure: 75% of all CBI programs are concentrated in small island states, highlighting the fiscal importance of investment migration for these economies.

Regionally, Europe and the Americas host the largest concentration of programs, with Asia also playing a significant role, particularly in RBI and Active Investor models. Africa, MENA, and the Pacific currently maintain fewer programs.

Yet the landscape is shifting: several MENA states are rapidly expanding investor-residence and golden visa initiatives as part of broader economic diversification strategies with notable examples being Saudi Arabia, Oman, Kuwait, etc.

Evolving nationality trends also point to shifting global demand, with increasing participation from advanced economies such as the United States and the United Kingdom. This shift is evidenced by Portugal’s approvals in April 2023, where U.S. nationals formed the largest applicant group.

Beyond structural patterns, the briefing identifies key strategic transformations that are reshaping the industry’s trajectory. These include the growth of mission-driven investment routes, greater personalization in investment options, expanding digitalization of application systems, more sophisticated multi-layered due diligence processes, and stronger commitments to transparency and public accountability. Collectively, these developments signal an industry moving toward more regulated, purpose-oriented, and institutionally credible models.

Taken together, these findings position investment migration as a dynamic and increasingly differentiated global field – one that serves both national development priorities and investor needs when underpinned by strong governance, sustainable design, and diversified investment pathways.