The Convention on the Rights of the Child establishes that “every child has the inherent right to life” and that States must ensure survival and development to the maximum extent possible (Art. 6), as well as provide protection and care necessary for well‑being, with the child’s best interests being a primary consideration in all actions affecting them (Art. 3)((United Nations. “Convention on the Rights of the Child.” United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner, 20 Nov. 1989, www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/convention-rights-child.)). From this foundation, affordable, high-quality childcare can be understood as a fundamental right, critical to fulfilling the Convention’s core principles.

Economic theory suggests that reducing the cost of childcare increases the returns to employment, which in turn encourages greater use of childcare services and boosts the likelihood that parents, particularly mothers, enter or remain in the workforce((Tekin, Erdal. “An Overview of the Child Care Market in the United States.” National Bureau of Economic Research, Oct. 2021, www.nber.org/sites/default/files/2021-10/White%20Paper-Tekin-101.06.21_revised.pdf.)).

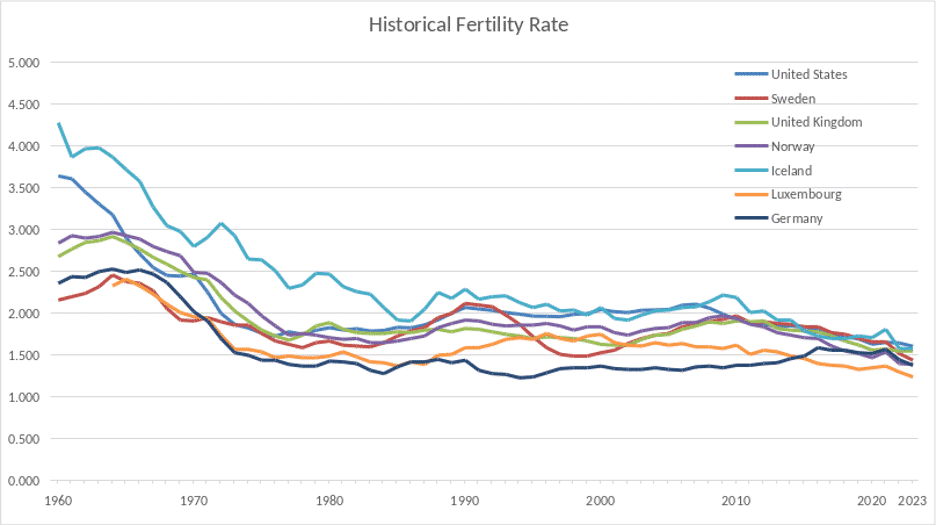

In reality, affordability remains a major barrier. In the United States, full-time center-based care consumes about 11% of family income on average, while home-based care requires 10%, both above the federal affordability benchmark of 7%. For low-income families, the burden is far heavier, with childcare costs consuming over four times that benchmark((National Institute for Early Education Research. “Child Care Is Unaffordable for Working Parents Who Need It Most.” NIEER, 15 Feb. 2019, https://nieer.org/research-library/child-care-unaffordable-working-parents-who-need-it-most)). Across the Atlantic, the European Union counted about 81 million children in early 2022, roughly 18% of its population, but their numbers have fallen by around 1 million over the past decade, even as the total population grew((UNICEF. The State of Children in the European Union. UNICEF, Feb. 2024, www.unicef.org/eu/reports/report-state-children-european-union.)).

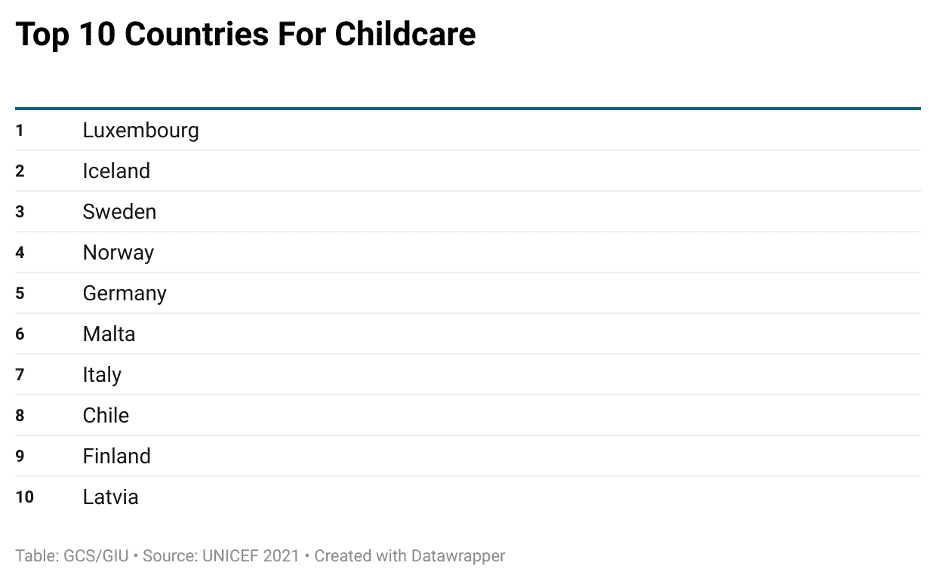

Nevertheless, some nations stand out as success stories. Luxembourg, Iceland, Sweden, Norway, and Germany continue to provide models of affordable, high-quality childcare that support both family life and strong labor market participation.

Childcare availability is integral to supporting parental employment, particularly among mothers, reducing economic dependency and poverty, while also playing a vital role in child development. When provided as a child’s right, it affirms society’s responsibility to ensure all children have adequate family care and access to non-family resources for the full development of their capabilities.

Affordability is a key factor: childcare costs act as a regressive tax on mothers’ labor supply, reducing returns from employment. With free services scarce, funding mechanisms become crucial for equitable access((Yerkes, Mara A., and Jana Javornik. “Creating Capabilities: Childcare Policies in Comparative Perspective.” Journal of European Social Policy, vol. 29, no. 4, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928718808421.. The broader issue can be framed as a market failure. High-quality childcare generates benefits for society beyond the immediate users, including lower long-term costs from poor education, reduced welfare dependence, and decreased crime and substance abuse rates((Tekin, Erdal. “An Overview of the Child Care Market in the United States.” National Bureau of Economic Research, Oct. 2021, www.nber.org/sites/default/files/2021-10/White%20Paper-Tekin-101.06.21_revised.pdf.)).

Cost remains one of the most significant barriers to securing childcare for families. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services defines childcare as affordable if it consumes no more than 7 percent of a family’s income. Yet, more than 60 percent of working parents in the United States exceed this threshold. On average, parents with children under age 14 spend about 10 percent of their income on center-based care, with a sharp divide by income level: low-income parents spend roughly 28 percent, compared to 8 percent for higher-income households((Tekin, Erdal. “An Overview of the Child Care Market in the United States.” National Bureau of Economic Research, Oct. 2021, www.nber.org/sites/default/files/2021-10/White%20Paper-Tekin-101.06.21_revised.pdf.)).

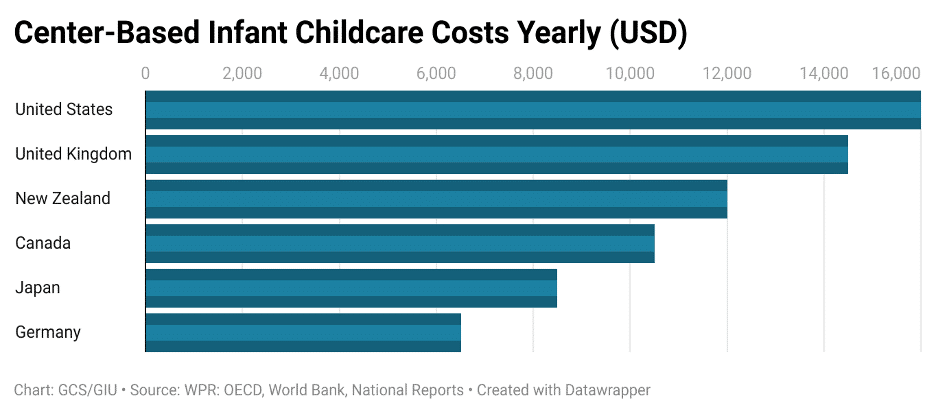

This affordability crisis has deepened in recent years, particularly under the economic pressures of the COVID-19 pandemic. Between January 2020 and September 2024, the cost of daycare and preschool rose by approximately 22 percent((Pew Research Center. “5 Facts about Child Care Costs in the US.” Pew Research Center, 25 Oct. 2024, www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2024/10/25/5-facts-about-child-care-costs-in-the-us/.)). Rising costs have placed further strain on families already struggling to meet the federal affordability benchmark, widening the gap between what childcare costs and what parents can reasonably pay.

When it comes to the United Kingdom, childcare costs can consume up to 75 percent of a parent’s income, a proportion that underscores systemic shortcomings in supporting working families. These costs are not only burdensome but also place the United Kingdom at the top of global rankings for childcare expenses. In 2022, it was identified as the most expensive country for childcare among developed nations, a reality that sparked significant public backlash. This frustration culminated in the “March of the Mummies” in October 2022, when thousands rallied nationwide to call for urgent reforms((Euronews. “Childcare Puzzle: Which Countries in Europe Have the Highest and Lowest Childcare Costs?” Euronews, 6 Mar. 2023, www.euronews.com/next/2023/03/06/childcare-puzzle-which-countries-in-europe-have-the-highest-and-lowest-childcare-costs.)).

Childcare affordability varies widely across Europe, with significant implications for labor force participation, gender equality, and child well-being. The urgency of equitable childcare provision is amplified by Europe’s child poverty rates: one in four children around 20 million are at risk of poverty or social exclusion in the EU((UNICEF. The State of Children in the European Union. UNICEF, Feb. 2024, www.unicef.org/eca/reports/state-children-eu.)). Affordable, high-quality childcare is therefore a critical tool for breaking cycles of poverty and ensuring equal opportunities from the earliest years.

Recognizing these challenges, EU leaders in 2025 designated Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) as a core social right, granting children the entitlement to a childcare place immediately after parental leave. Yet in many member states, this remains aspirational. Only a few, such as Denmark, Germany, Estonia, Slovenia, Finland, Sweden, and non-EU Norway, have closed the ECEC gap, guaranteeing universal, uninterrupted access((European Commission. Key Data on Early Childhood Education and Care in Europe – 2025. Eurydice, 2025, https://eurydice.eacea.ec.europa.eu/publications/key-data-early-childhood-education-and-care-europe-2025.

Comparative research further shows clear differences between public and market-based childcare systems. A study of six countries found that public models, as in Iceland, Slovenia, and Sweden, tend to provide more accessible, available, affordable, and higher-quality services, though flexibility remains limited. In contrast, market-driven systems, such as those in Australia, the Netherlands, and the UK, lag in all these areas, with parents in non-standard work or job-seeking facing the greatest challenges((Yerkes, Mara A., and Jana Javornik. “Creating Capabilities: Childcare Policies in Comparative Perspective.” Journal of European Social Policy, vol. 29, no. 4, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928718808421..

The five countries below stand out for providing affordable childcare while also maintaining high quality standards and broad accessibility based on UNICEF’s assessment:

Luxembourg

Luxembourg operates one of the world’s most affordable childcare systems, built on generous public funding and fee subsidies. An income-based “service voucher” scheme can reduce fees to zero for low-income families and provides 20 hours per week of free care for all children aged 1–4, regardless of income((European Commission. “Early Childhood and School Education Funding.” Eurydice, 27 Nov. 2023, https://eurydice.eacea.ec.europa.eu/eurypedia/luxembourg/early-childhood-and-school-education-funding. The country spends about 1.7% of GDP, roughly $17,000 PPP per child annually on early education, the highest among OECD members. Quality is assured through accreditation requirements, trained staff, and a national multilingual curriculum.

Sweden

Sweden limits childcare costs through its national maxtaxa policy: parents pay no more than 3% of income for the first child, 2% for the second, and 1% for the third((European Commission. “Early Childhood and School Education Funding.” Eurydice, 2025 https://eurydice.eacea.ec.europa.eu/eurypedia/sweden/early-childhood-and-school-education-funding. The country invests 1.6% of GDP in early childhood education, funding well-trained preschool teachers, a play-based curriculum, and favorable staff ratios. Access is near-universal, with every child entitled to a place from 12 months and 91% enrolled by age 3.

Iceland

In Iceland, municipal subsidies keep full-time childcare fees low, about ISK 25,000–35,000 ($200–$280) per month and the country matches Sweden in devoting 1.7% of GDP to early education. Child-to-staff ratios are among the best in the OECD (as low as 1:5) and enrolment is almost universal, with 95% of two-year-olds and 96% of children aged 3–5 attending preschool. However, there are still certain challenges, including an increasing shortage of childcare options for children aged 12 months to two years in Iceland. Both childminders (“day-mothers”) and preschools are in limited supply. With approximately 60% of Iceland’s 372,000 residents living in the Reykjavik area, the demand is particularly high there. Over the past 15 years, about 1,000 children annually across Iceland have been unable to access preschools or daycare services((“Best Childcare in the World? Maybe So, but New Parents in Iceland Are Holding Out.” Child Care Canada, 25 May 2023, https://childcarecanada.org/documents/child-care-news/23/05/best-childcare-world-maybe-so-new-parents-iceland-are-holding-out)).

Norway

Norway limits parental fees to a maximum of about NOK 3,000 ($290) per month, with additional subsidies offering 20 hours per week free for low-income families. This keeps costs at roughly 6% of income. Public spending is about 1.0–1.1% of GDP, among the highest per child globally. There should be at most 3 children per staff member under age 3, and 6 children per staff member over age 3((Norway, Ministry of Education and Research. “Early Childhood Education and Care Policy.” Regjeringen.no, https://www.regjeringen.no/en/topics/families-and-children/kindergarden/early-childhood-education-and-care-polic/id491283/.)), ensuring favorable ratios. Strict qualification requirements, low ratios, and a national curriculum maintain quality.

Germany

Germany has sharply improved affordability and access since introducing a legal entitlement to childcare from age 1 in 2013. Fees are heavily subsidized, and in many areas care for ages 3–5 is free. Quality is supported by public investment and regulated standards, with availability steadily expanded through legal guarantees((European Commission. “Early Childhood Education and Care.” Eurydice, https://eurydice.eacea.ec.europa.eu/eurypedia/germany/early-childhood-education-and-care. However, in numerous regions, particularly urban areas, there is a significant shortage of childcare spots. Parents frequently face waiting periods of months or even years to secure a place, compelling many to cut back on work hours or postpone their return to employment((“Where Childcare Costs More Than Rent.” WPR Newsletter, https://wpr-newsletter.beehiiv.com/p/where-childcare-costs-more-than-rent.)).

As demonstrated above, countries of varying income levels, including Malta, Italy, Chile, Finland, and Latvia, have all invested in making childcare more accessible and affordable, yielding significant benefits. Malta’s universal free childcare scheme (launched 2014) nearly quintupled enrollment and helped raise female labor participation from about 40% to over 70%((Debono, James. “Malta’s Female Participation Rate Grows Faster than EU’s.” MaltaToday, 2023, www.maltatoday.com.mt/news/national/122622/maltas_female_participation_rate_grows_faster_than_eus.)). Italy’s recent recovery plan allocates €4.6 billion to expand childcare places by 76% by 2025, aiming to increase under-3 enrollment and promote female employment((“New Welfare Policy Response to Address Low Fertility Levels.” European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, World Health Organization, 2023, eurohealthobservatory.who.int/monitors/health-systems-monitor/updates/hspm/italy-2023/new-welfare-policy-response-to-address-low-fertility-levels.)). In Latvia, 34% of children aged 0–2 in both the lowest and highest income groups attend early childhood education and care (ECEC), showing equal access across income levels, unlike most OECD countries((Education at a Glance 2024: Latvia. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2024, www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2024/09/education-at-a-glance-2024-country-notes_532eb29d/latvia_9e902bcb/5c8d1469-en.pdf.)). These diverse cases show that quality childcare can be prioritized and delivered even outside the wealthiest nations.

Overall, as displayed, affordable childcare is vital for children’s development, parental employment, and economic growth. Many countries, including the United States and the United Kingdom, face serious affordability challenges that limit access and deepen inequality. In contrast, nations such as Luxembourg, Sweden, Iceland, Norway, and Germany show that strong public investment, clear standards, and universal access can make childcare both affordable and high quality. Publicly funded childcare systems consistently deliver fairer outcomes, recognizing care as a basic right and ensuring benefits reach the whole of society. Adopting these proven approaches can close affordability gaps, improve opportunities for children, and promote a more inclusive labor market.