In the 21st century, the concept of citizenship is undergoing a profound evolution. Traditionally tied to political and national identity, citizenship is increasingly viewed through a pragmatic lens, treated as a strategic asset for navigating the uncertainties of a volatile world. Globalization, political polarization, and economic instability have played significant roles in reshaping the meaning of citizenship, moving it beyond its historical role as a marker of allegiance to a state.

This transformation is further accelerated by the growing accessibility of information, territories, mobility services, and visa programs. Advances in technology and globalization have made it easier for individuals to navigate legal frameworks and explore new opportunities across borders. As a result, citizenship has evolved into a flexible and adaptive asset, aligning with personal and professional aspirations in an interconnected world.

Despite the polarizing debates surrounding global mobility, this trend offers mutual benefits for individuals, host nations, and countries of origin. Residency programs and multiple citizenship enhance quality of life, mobility, access to better public services and more beneficial fiscal regimes providing a safety net against instability. For host countries, these programs attract foreign direct investment (FDI), skilled labor, and demographic renewal. Origin countries, meanwhile, benefit significantly from remittances that support household needs, education, and healthcare, and knowledge exchange and innovation through diaspora networks. Additionally, the return of skilled individuals can lead to brain gain and human capital development, contributing to long-term economic growth.

This paper examines the strategic redefinition of citizenship and its far-reaching implications for individuals, nations, and the global landscape. Additionally, it explores practical strategies that individuals can employ to enhance their global mobility in an increasingly dynamic and interconnected world.

Historically, citizenship has been rooted in the concept of political belonging and allegiance to a nation-state. Political theorists like T.H. Marshall (1950) framed citizenship as a triad of civil, political, and social rights existing within defined territorial boundaries.((Marshall, T. H. (1950). Citizenship and social class, and other essays. Cambridge University Press, pp. 10-1.)) Marshall’s model emphasized a reciprocal relationship between the individual and the state, portraying citizenship as a lasting bond based on loyalty, participation, and mutual obligation. Marshall’s seminal work, Citizenship and Social Class, outlined civil rights as encompassing legal protections, political rights as the ability to participate in governance, and social rights as access to welfare and equality.((Marshall, T. H. (1950). Citizenship and social class, and other essays. Cambridge University Press, pp. 10-1.)) This traditional view positioned citizenship as a marker of national identity, deeply tied to the legal and political framework of the state.

During the mid-20th century, this model reflected the priorities of post-war societies, particularly the expansion of social welfare programs and democratic inclusion. However, as globalization accelerated in the latter half of the century, the territorial and static nature of Marshall’s framework faced challenges. Citizenship began to evolve into a more fluid and multi-dimensional concept, influenced by transnational movements and global economic integration.

Yasemin Soysal expanded this discourse with her theory of post-national citizenship, introduced in Limits of Citizenship (1994). She argued that globalization and international human rights frameworks had effectively decoupled citizenship from national borders.((Soysal, Y. N. (1994). Limits of citizenship: Migrants and postnational membership in Europe. University of Chicago Press, pp. 136-67.)) Individuals could now also claim rights based on universal principles rather than solely on allegiance to a specific state. This shift, driven by organizations like the United Nations and regional entities such as the European Union, reshaped the concept of citizenship by emphasizing its transnational character mainly regarding the protection of individuals human rights. Over time, treaties, supranational courts, and advocacy networks further reinforced the idea of citizenship beyond borders, particularly benefiting refugees, migrants, and global citizens seeking rights unattainable in their countries of origin.((Human rights laws and treaties have been pivotal in relativizing the traditional concept of citizenship as exclusively tied to a specific territory. Supranational courts, organizations, and advocacy networks have played a central role in this transformation by ensuring that universal principles take precedence over national boundaries. The European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR), for instance, in Soering v. United Kingdom (1989), reinforced the idea that states must adhere to human rights standards beyond their borders, protecting individuals from inhumane treatment. Similarly, the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) in Chen v. Secretary of State for the Home Department (2004) and Metock v. Ireland (2008) upheld the rights of individuals to move and reside freely across the EU, irrespective of traditional territorial restrictions. Organizations such as Amnesty International and the International Organization for Migration (IOM) have championed these principles by advocating for the rights of refugees and migrants under frameworks like the 1951 Refugee Convention. These efforts, combined with landmark cases, demonstrate how human rights frameworks have decoupled citizenship from strict territoriality, advancing a post-national vision of membership and rights.)) Additionally, the decoupling of citizenship from strict territoriality, as advanced by human rights laws, treaties, and the work of supranational courts and advocacy organizations, directly addresses the challenges of statelessness, a context were individuals face profound and far-reaching consequences due to the lack of nationality.((Stateless individuals, by definition, lack a legal bond to any nation-state, leaving them without access to fundamental rights and protections typically granted through citizenship. Human rights frameworks, such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), which affirms the right to nationality (Article 15), have been instrumental in mitigating the effects of statelessness by asserting that rights are inherent to all individuals, not contingent on citizenship.))

As critical theorist Étienne Balibar cautionary notes, while citizenship defines inclusion, it simultaneously excludes those deemed outsiders, often reinforcing inequality and marginalization.((Balibar, É. (2015). Citizenship. Polity Press, pp. 57-66.)) His critique gained prominence as migration crises and restrictive immigration policies highlighted the tension between universal rights and national sovereignty. In this regard, stateless individuals epitomize the exclusionary dimensions of citizenship that Balibar highlights, as they are systematically denied the membership and rights that citizenship affords. Statelessness exposes the paradox Balibar critiques: while citizenship is framed as a mechanism for universal rights and belonging, it simultaneously operates as a gatekeeping tool that marginalizes those without legal ties to a nation-state.

Aihwa Ong took the conversation further, reframing citizenship as a strategic tool for navigating global systems.((Ong, A. (1999). Flexible citizenship: The cultural logics of transnationality. Duke University Press, p. 6.)) She observed how individuals increasingly sought multiple citizenships to maximize personal and economic opportunities, treating citizenship as a flexible asset rather than a static identity. This concept gained traction during the late 1990s with the rise of global capital flows, international mobility, and the emergence of transnational elites. Programs such as citizenship and residence-by-investment (RCBI) and digital nomad visas (DNV) exemplify the growing importance of flexibility in citizenship, enabling individuals to navigate and benefit from diverse legal, economic, and social systems across borders. These initiatives also demonstrate the recognition by both individuals and states that citizenship has evolved from its traditional foundation of political allegiance into a dynamic and practical tool.

The evolution of citizenship is highly dynamic., reflects its dynamic nature. Academia’s perspectives showcases how citizenship has transformed in response to globalization, mobility, and the changing relationship between individuals and states. Today, citizenship serves as a gateway to pursue different life projects, offering opportunities for mobility, economic advancement, and personal growth in an increasingly interconnected world.

Although it is commonly understood that an increasing number of people are acquiring second or multiple citizenships, estimating the global number of individuals holding multiple citizenships remains a complex challenge. This difficulty arises from the wide variation in national laws regarding dual or multiple citizenship, as well as the absence of standardized, comprehensive data collection on this phenomenon. Some countries actively track and report dual citizenship, while others do not, and individuals may not always disclose their additional citizenships. As a result, while the trend toward multiple citizenships is evident, precise global figures are elusive, highlighting the need for more coordinated international efforts to better understand this growing aspect of global mobility and identity.

In the United Kingdom, the number of dual citizens in England and Wales surged from 613,000 (1.1% of the population) in 2011 to 1,236,000 (2.1%) by 2021, highlighting a growing trend toward dual nationality acceptance.((Office for National Statistics. (2023). Dual citizens living in England and Wales: Census 2021. Retrieved from https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/internationalmigration/articles/dualcitizenslivinginenglandandwales/census2021)) Similarly, in Canada, nearly one in five residents is a naturalized citizen, many of whom retain their original nationality, resulting in millions of dual citizens.((Statistics Canada. (2022). Immigrants make up the largest share of the population in over 150 years and continue to shape who we are as Canadians. Retrieved from https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2021/as-sa/98-200-X/2021008/98-200-X2021008-eng.cfm))

In the European Union (EU), dual citizenship is particularly prevalent due to the region’s interconnected legal and cultural frameworks. By 2020, over 15 million EU residents were estimated to hold dual or multiple citizenships.((Eurostat. (n.d.). Acquisition of citizenship statistics. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Acquisition_of_citizenship_statistics)) In 2022, EU Member States granted citizenship to 989,900 individuals residing within their territories, marking a 20% increase compared to 2021. This surge highlights the growing trend of naturalization within the EU, where 2.6 out of every 100 non-national residents secured citizenship.((Eurostat. (n.d.). Acquisition of citizenship statistics. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Acquisition_of_citizenship_statistics))

Germany, with its large immigrant population, reported approximately 4.3 million dual citizens in 2019((According to the German Federal Statistical Office (Destatis), the number of British citizens acquiring German citizenship increased from approximately 600 in 2015 to 14,600 in 2019, a rise attributed to the Brexit referendum in 2016. Federal Statistical Office of Germany (Destatis). (2020, June). Record number of British citizens naturalized in Germany in 2019. Retrieved from Federal Statistical Office of Germany (Destatis). (2020, June). Record number of British citizens naturalized in Germany in 2019. Retrieved from https://www.destatis.de/EN/Press/2020/06/PE20_197_12511.html and IamExpat Germany. (2019). Steep rise in the number of people granted German citizenship in 2019. Retrieved from https://www.iamexpat.de/expat-info/german-expat-news/steep-rise-number-people-granted-german-citizenship-2019)), while France leads with an estimated 5–6 million dual citizens (including overseas territories and French citizens living abroad), reflecting its decades-long policy of tolerance toward multiple nationalities.((Alternatives Économiques. (2016). Part de binationaux parmi les immigrés devenus français selon leur pays d’origine.Retrieved from https://www.alternatives-economiques.fr/part-de-binationaux-parmi-immigres-devenus-francais-selon-pays-dorigine-010220168918.html)) While Germany and France lead in numbers, Italy’s jus sanguinis policies extend citizenship rights to millions worldwide.((Tintori, G. (2012, November 21). More than one million individuals got Italian citizenship abroad in twelve years (1998-2010). GLOBALCIT. https://globalcit.eu/more-than-one-million-individuals-got-italian-citizenship-abroad-in-the-twelve-years-1998-2010/)) EU-wide freedom of movement further encourages cross-national naturalizations. This trend not only reflects changing national policies but also facilitates economic integration and cultural exchange across borders, reinforcing the significance of dual citizenship in a globalized world.

The phenomenon extends beyond Europe and North America. In Australia, where over 30% of the population was born overseas, dual citizenship is a practical reality for millions.((Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). (2023). Australia’s population by country of birth, June 2023. Retrieved from https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/population/australias-population-country-birth/latest-release)) Nigeria, with its large expatriate communities in countries like the United Kingdom, also boasts millions of dual citizens.((For instance, the 2021 Census in England and Wales recorded approximately 34,700 dual citizens holding both Nigerian and British passports. Office for National Statistics (ONS). (2021). Dual citizens living in England and Wales: Census 2021. Retrievedfrom https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/internationalmigration/articles/dualcitizenslivinginenglandandwales/census2021)) Meanwhile, Brazil sees substantial numbers of dual citizens tied to historical migration patterns with countries like Portugal and Italy.((As of 2023, there were 799,209 Italian citizens residing in Brazil. Projections indicate that this number could reach 1.2 million by 2030. It is also relevant to mention that many italo-brasilian nationals do not reside in Brazil. Italianismo. (n.d.). Number of Italians in Brazil expected to reach 1.2 million by 2030. Retrieved from https://italianismo.com.br/en/numero-de-italianos-no-brasil-deve-atingir-12-milhao-ate-2030/)) These examples underscore the role of migration and flexible citizenship policies in shaping a global trend toward dual or multiple national affiliations.

The increasing acceptance of dual and multiple citizenships reflects a fundamental shift in the perception of nationality, transforming it from a rigid, singular identity into a flexible and strategic asset. No longer seen as an act of disloyalty, multiple citizenship is now widely recognized as a natural consequence of global mobility and interconnected societies. As nations adapt to these evolving realities, it has become increasingly difficult for states to deny or refuse recognition of dual or multiple citizenships. Given these trends, the number of individuals holding multiple nationalities is expected to rise significantly, further reinforcing the fluid and dynamic nature of modern citizenship.

Therefore, in the contemporary globalized world, Vink et. al. sustain, restrictions on dual or multiple citizenships are increasingly viewed as arbitrary, as migrants often maintain active transnational connections (social, economic, and political) with their countries of origin. This dynamic has led to growing pressure on political elites from expatriate communities to permit naturalization abroad while preserving legal ties with their home countries.((Vink, M., Schakel, A. H., Reichel, D., Luk, N. C., & de Groot, G.-R. (2019). The international diffusion of expatriate dual citizenship. Migration Studies, 7(3), 362–383.))

According to Vink et. al. these five trends collectively contribute to the growing global tolerance to multiple citizenship:

- Citizenship as a Choice: While birthright remains the primary form of citizenship attribution, the idea of citizenship as a choice rather than an innate status is increasingly accepted, emphasizing individual rights in both acquisition and loss of citizenship. Although Human Rights law promotes the elimination of statelessness.

- Gender Equality in Citizenship: Discrimination between men and women in citizenship acquisition has decreased, allowing for facilitated naturalization in mixed marriages and enabling children of such unions to hold multiple citizenships automatically at birth.

- Pressures from Expatriates: Diversifying international migration has led to origin states facing increased pressure from expatriates who wish to acquire citizenship in prime destination countries.

- Reduced Concerns About Dual Allegiances: Economic development, democratization, and reduced intra-state conflicts have made dual allegiances less of a concern compared to the past.

- Post-National Rights Framework: In a world where rights are increasingly defined at supranational levels, the idea that a nation-state can demand exclusive allegiance from its members is becoming less tenable.

The increasing acceptance of dual and multiple citizenships is a direct result of the legal, social, political, and economic transformations that have accompanied globalization. In this evolving global landscape, citizenship laws are adapting to the realities of transnational connections, making multiple citizenship not only more common but also more widely recognized as a legitimate and integral part of modern society.

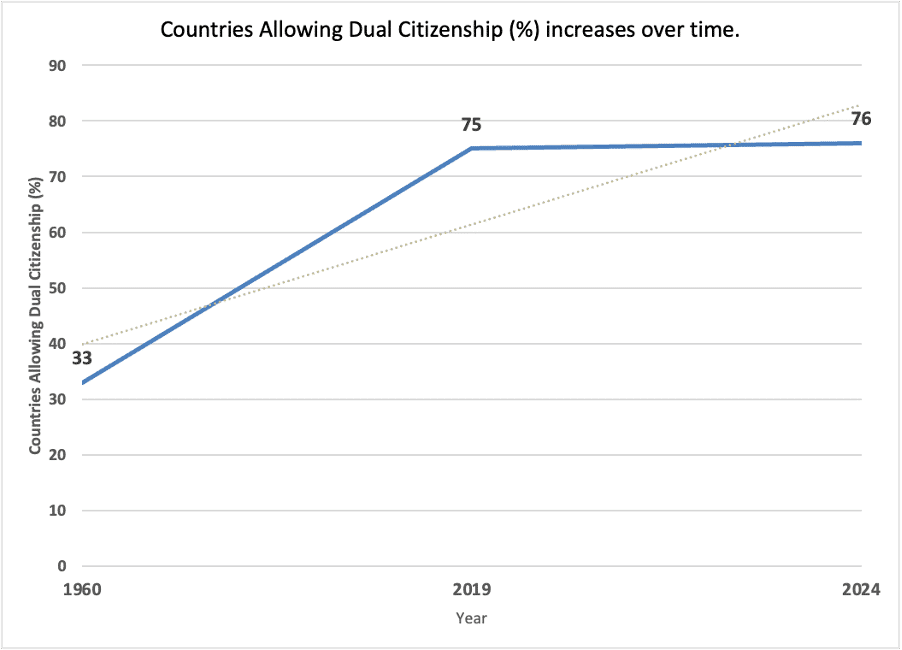

From a state perspective, in 1960, only about one-third of countries permitted dual citizenship, but by 2019, this number had grown to approximately 75%, demonstrating increasing acceptance. Regional variations persist, with global averages reaching 76% by 2020.((Maastricht University. (n.d.). Dual citizenship database. MACIMIDE. Retrieved December 5, 2024, from https://macimide.maastrichtuniversity.nl/dual-cit-database/)) Despite this progress, challenges remain. Many nations do not systematically track dual citizenship holders, and legal complexities (such as conditional permissions or outright bans) further complicate global estimates. While exact numbers are elusive, the growing acceptance of dual and multiple citizenships underscores evolving perspectives on national identity and globalization, as more individuals embrace the opportunities provided by flexible and transnational affiliations.

This shift in global mobility offers significant benefits to destination countries, enabling them to attract talent, investment, and innovation that drive economic growth and competitiveness. Programs tailored for digital nomads, retirees, and entrepreneurs often bring in individuals who contribute to local economies through consumption, taxation, and the establishment of businesses. Entrepreneurial and talent visas, for instance, attract highly skilled professionals and creative innovators who bolster key industries, stimulate job creation, and enhance technological advancement.((Global Citizen Solutions. (n.d.). How immigration is revitalizing Portugal’s economy and addressing the public deficit. Global Intelligence Unit. Retrieved from https://www.globalcitizensolutions.com/intelligence-unit/briefings/how-immigration-is-revitalizing-portugals-economy-and-addressing-the-public-deficit/)) Additionally, retirees relocating through favorable visa schemes bring steady income streams, often drawn from pensions or savings, which they spend on housing, healthcare, and other services, injecting liquidity into local markets.((Madrid, L. (n.d.). International Retirement Migration (IRM) and the recent American Diaspora: motivations and alternatives. Global Intelligence Unit. Retrieved from https://www.globalcitizensolutions.com/intelligence-unit/reports/retirement-guide-for-us-citizens/international-retirement-migration/))

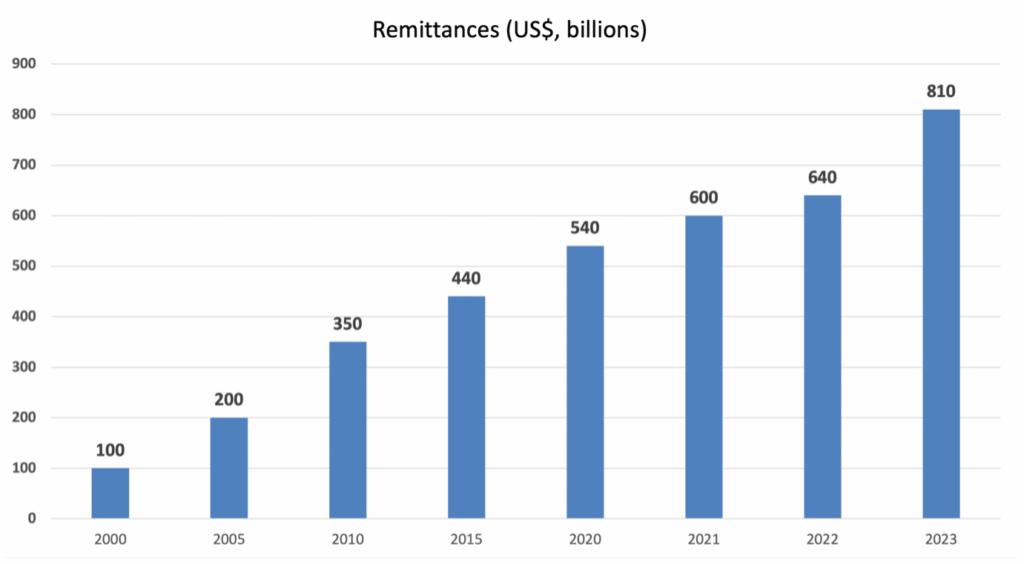

Origin countries also benefit significantly through strengthened diaspora connections, which foster economic growth and cultural exchange. Migrants often maintain strong ties to their home countries, sending remittances that play a crucial role in supporting local economies (remittances surpassed $800 billion globally in 2023, according to the World Bank)((World Bank. (2023, December 18). Remittance flows grow in 2023 but at a slower pace, says World Bank’s Migration and Development Brief. World Bank. Retrieved from https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2023/12/18/remittance-flows-grow-2023-slower-pace-migration-development-brief)).

Beyond financial contributions, diasporas act as cultural ambassadors and conduits for knowledge transfer, returning with new skills, global networks, and innovative practices that benefit their countries of origin. Moreover, diasporas often engage in philanthropic activities or invest in their home countries, funding education, healthcare, and infrastructure projects. By leveraging these connections, countries of origin can create mutually beneficial relationships with their citizens abroad, ensuring that global mobility becomes a tool for inclusive growth and development on both sides.

Citizenship has long been one of the most well-established concepts within the framework of nation-state laws, traditionally serving as a definitive marker of legal membership, rights, and obligations tied to a specific territorial and political entity. As highlited by Balibar, it provided a clear distinction between those included within a state’s jurisdiction and those considered outsiders. However, this fixed and territorially bound understanding of citizenship is evolving in response to globalization, transnational mobility, and the increasing influence of international human rights frameworks. As mentioned, today, citizenship is no longer solely defined by allegiance to a single nation-state but is increasingly seen as a flexible and strategic tool, shaped by universal principles and global systems.

This evolving nature of citizenship reflects the growing influence of globalization, transnational mobility, and international human rights frameworks, which have decoupled citizenship from its strict territorial roots. In this brief, we focus on what we call adaptive citizenship, exploring how this concept not only empowers individuals but also brings substantial benefits to both origin and destination states, fostering mutual prosperity and collaboration in an interconnected world.

Yossi Harpaz coined the term “citizenship 2.0” to describe the evolution of citizenshipbranding it a “global insurance policy.”((Harpaz, Y. (2019). Citizenship 2.0: Dual nationality as a global asset. Princeton University Press.)) In a world increasingly marked by geopolitical instability, economic crises, and environmental challenges, individuals are leveraging citizenship not just as a marker of identity but as a tool for mobility, security, and access to resources. Sociologist Thomas Faist complements this perspective by emphasizing the “denationalization” of citizenship, where its value lies in its transnational utility rather than allegiance to a single nation-state.((Faist, T. (2000). The volume and dynamics of international migration and transnational social spaces. Oxford University Press, pp. 197-9.))

This shift has significantly altered attitudes toward dual and multiple citizenships. Historically, dual citizenship was viewed with skepticism, particularly in countries like the United States, where it was often regarded as unpatriotic.((Faist, T. (2000). The volume and dynamics of international migration and transnational social spaces. Oxford University Press, chapter 7.)) However, in the 21st century, it has become a widely accepted and even sought-after asset. Harpaz highlights how dual citizenship has transitioned into a strategic contingency plan, particularly for high-net-worth individuals (HNWIs). For these individuals, holding multiple citizenships offers critical advantages, such as the ability to access rights, relocate swiftly, and safeguard assets during periods of political or economic instability.((Harpaz, Y. (2019). Citizenship 2.0: Dual nationality as a global asset. Princeton University Press.))

The growing popularity of dual and multiple citizenships is also driven by the expansion of global mobility and the increasing interdependence of economies. With the rise of transnational careers, remote work, and global markets, having access to multiple jurisdictions enhances personal and professional opportunities. It allows individuals to navigate international systems more effectively, whether for education, healthcare, or business purposes. Harpaz notes that this trend is particularly prominent in regions with strong economic or political networks, such as the European Union, where citizenship offers access to an entire bloc of nations.((Harpaz, Y. (2019). Citizenship 2.0: Dual nationality as a global asset. Princeton University Press.))

Governments have also adapted to this shift, recognizing the potential economic benefits of granting citizenship or residency to foreign nationals. Programs like CBI and golden visas have proliferated in recent decades, allowing individuals to acquire second citizenship in exchange for significant economic contributions. These programs have not only generated substantial revenue for host countries but also attracted skilled professionals, entrepreneurs, and investors. Faist suggests that this trend reflects the instrumentalization of citizenship as a mutually beneficial exchange between individuals and states.((Faist, T. (2000). The volume and dynamics of international migration and transnational social spaces. Oxford University Press, pp. 190.))

This shift toward instrumental citizenship is not without its critics. Scholars such as Rainer Bauböck argue that reducing citizenship to a purely transactional relationship risks undermining its essential role as “a foundation for political community and democratic participation”((Bauböck, R. (2018). Genuine links and useful passports: Evaluating strategic citizenship. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 45(6), p. 3.)). While dual and multiple citizenships undeniably offer significant benefits, including enhanced mobility and security, they also raise pressing questions about equity and inclusion.

Étienne Balibar however critiques the historical reliance of citizenship on its necessary link to the nation-state, highlighting its dual role as a mechanism of inclusion and exclusion. Balibar asserts that citizenship “defines insiders by designating outsiders,” often reinforcing social hierarchies and marginalizing those without formal ties to a state.((Balibar, É. (2015). Citizenship. Polity Press, p. 58.)) This perspective challenges the notion that citizenship inherently fosters community, emphasizing instead how it has been instrumentalized to exclude.

Dimitry Kochenov adds another layer to this critique by challenging the jus sanguinis principle of citizenship acquisition. He describes it as “a relic of feudal systems”((Kochenov, D. (2019). Citizenship and its absence. Cambridge University Press, p. 45.)) that privileges lineage over CBI programs and other forms of nationality acquisition based on invetment, donation and special achievement. Additionally, the jus sanguinis principle often contrasts with the often stricter requirements of naturalization processes, which demand significant economic, cultural, or legal commitments. These entrenched inequalities highlight the need to reimagine citizenship frameworks to address the complex and transnational realities of the modern world.

Whether tied to international protection for refugees and stateless individuals, investor visas, retirement migration, digital nomad programs, citizenship by descent laws, or CBI schemes, these evolving pathways for granting citizenship represent a significant shift in breaking the traditional glass ceiling of nation-states. These frameworks enable a broader range of individuals to access the rights and opportunities afforded by citizenship in various jurisdictions, fostering greater inclusion and adaptability in an interconnected world.

It is clear that the evolving perception of citizenship reflects the complexities of a globalized world. From its roots as a symbol of political identity to its modern role as a strategic asset, citizenship has become a dynamic and multifaceted tool. This transformation, as articulated by Harpaz, Faist, and Ong underscores the growing importance of mobility, security, and transnational connections in shaping individual and collective futures.

In the evolving discourse on citizenship, we propose the concept of adaptive citizenship to encapsulate the dynamic and strategic ways in which citizenship now functions in response to global transformations. Adaptive citizenship refers to the redefinition of citizenship as a flexible, instrumental, and transnational tool that aligns with the diverse needs of individuals and states in an interconnected world. This term denotes and advocates for a positive perspective on the evolution of citizenship, emphasizing its capacity to adapt constructively to the challenges and opportunities of globalization. Unlike traditional citizenship, rooted in static ties to a nation-state, adaptive citizenship highlights fluidity, allowing individuals to navigate global systems for mobility, security, and opportunity while enabling states to attract talent, investment, and innovation. It reflects the growing understanding of citizenship not as a singular legal or political identity but as a customizable framework shaped by individual aspirations and global realities.

Citizenship’s instrumental value has grown in a world where uncertainty is the norm, serving as a vital tool for enhancing global mobility and securing personal and financial stability. A strong passport enables individuals to bypass travel restrictions, establish businesses in stable economies, and secure rights that might not be available in their country of origin. As volatility reshapes global dynamics, dual, multiple or alternative citizenship is increasingly seen as a strategic asset, a “Plan B”, offering protection and flexibility in an unpredictable world.((Casaburi, P. (2025, January 15). What’s next for investment migration in 2025. Medium. Retrieved from https://medium.com/global-citizen-solutions/whats-next-for-investment-migration-in-2025-0aaf4cf81382))

Plan B is often driven by the pursuit of a better lifestyle and enhanced quality of life, including access to superior healthcare, education, safety, and overall well-being. Many individuals seek opportunities or destinations with world-class infrastructure, efficient public services, and a high standard of living that supports personal and professional fulfillment. Cultural experiences also play a key role, as people look to immerse themselves in diverse environments, explore new traditions, and benefit from the opportunities that global connectivity offers

HNWIs frequently seek a second passport or an alternative residence to optimize tax benefits, diversify investments, and gain access to thriving financial markets, while professionals and entrepreneurs move to business-friendly jurisdictions that provide global career prospects and economic opportunities. Digital nomads and remote workers prioritize destinations with strong digital infrastructure, flexible visa policies, and vibrant expatriate communities that support location-independent lifestyles. Retirees are increasingly choosing countries with lower living costs, pleasant climates, and high-quality social and healthcare services.

Climate change considerations are also influencing migration patterns, with individuals and families seeking regions less vulnerable to extreme weather events and environmental risks.((Looking ahead, projections indicate a significant increase in climate-related migration. The World Bank’s Groundswell report estimates that climate change could force 216 million people across six world regions to move within their countries by 2050. World Bank. (2021, September 13). Climate change could force 216 million people to migrate within their own countries by 2050. World Bank. Retrieved from https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2021/09/13/climate-change-could-force-216-million-people-to-migrate-within-their-own-countries-by-2050)) At the same time, political instability, economic uncertainty, and restrictive regulatory environments remain significant push factors, prompting individuals to seek more stable and secure jurisdictions where they can safeguard their personal and financial futures. The year of 2024, named as the coincided with rising political polarization and economic uncertainty, fueling a surge in individuals seeking relocation and second citizenships as part of a strategic “Plan B.”

Following the U.S. presidential election, affluent Americans increasingly explored golden visas and second citizenships in countries like Malta and Portugal to secure greater global mobility and mitigate domestic instability. Google searches for “easiest countries to get citizenship” spiked by over 1,000% on November 6, 2024, the day after the election, highlighting growing concerns over political divisions. Similarly, in the United Kingdom, high taxes and changes to non-domiciled tax status have driven wealthy individuals to seek residency-through-investment programs in Greece, Portugal, and Spain, benefiting from favorable tax conditions and Schengen travel freedoms.

Meanwhile, recent political shifts and economic challenges in Europe have accelerated demand for golden visas and passports in countries like Hungary, Greece, Italy, the UAE, and various Caribbean nations. These developments underscore how political and economic uncertainty worldwide is pushing individuals to seek alternative citizenships, reinforcing the growing role of investment migration in a rapidly shifting geopolitical landscape.

RCBI programs, Digital Nomad, Passive Income and talent visas and reflect the principles of adaptive citizenship by offering individuals strategic options to navigate global uncertainties, such as political instability, economic volatility, or environmental risks. They empower individuals to diversify their legal affiliations, secure alternative residency or citizenship, and align their personal goals with global opportunities while meeting states’ needs for investment, talent, and demographic renewal.

There are numerous visas and investment migration programs designed to enable individuals to develop their life projects in new countries. These programs provide opportunities for people to relocate, pursue careers, retire, or secure better quality of life and opportunities for their families. Through such schemes, individuals can either gain direct access to citizenship, as in the case of CBI programs, or accumulate residency time under specific visas, such as golden visas (RBI schemes), retirement visas, or digital nomad visas, to qualify for citizenship in the future. This flexibility allows individuals to align their personal aspirations with global opportunities while navigating the challenges of an increasingly interconnected and dynamic world. In the following sections, we will explore some of these options, highlighting how they cater to diverse needs and circumstances.

The transformation of citizenship from a fixed national identity to a strategic asset underscores the evolving nature of global mobility. In an era marked by geopolitical instability, economic volatility, and shifting regulatory landscapes, individuals are increasingly leveraging diverse migration pathways, such as RCBI programs, DN visas, and passive income schemes to secure personal and financial stability. The ability to relocate, obtain residency, and even acquire alternative citizenships has become a vital tool in navigating uncertainty, allowing individuals to align their legal affiliations with their professional aspirations, lifestyle preferences, and long-term security needs. This evolution highlights the adaptability of citizenship as both a privilege and an instrument of resilience in an interconnected world.

Strategic migration choices are not solely driven by necessity but increasingly by opportunity and contingency planning. High-net-worth individuals, entrepreneurs, digital nomads, and retirees are actively seeking jurisdictions that offer tax advantages, enhanced global mobility, and superior quality of life. Digital nomads, for example, use their original passport privileges to work remotely across borders, but others leverage digital nomad visas in some jurisdictions.

From a policy perspective, governments are recognizing the mutual benefits of strategic mobility. Countries offering RBI and CBI programs attract foreign direct investment (FDI), bolster real estate markets, and support economic revitalization.

Meanwhile, digital nomad and talent visa programs help nations attract global professionals who contribute to local economies without burdening social services. Retirement visas and tax incentives for expatriates provide another economic boost, ensuring steady capital inflows while mitigating demographic challenges. These programs reinforce the notion of citizenship as an adaptive legal framework rather than a rigid national allegiance, demonstrating that states and individuals alike are reshaping the traditional concepts of belonging and mobility.

As the global landscape continues to evolve, the future of citizenship will be defined by its flexibility, strategic utility, and responsiveness to individual and economic needs. Whether through alternative passports, long-term residency planning, or digital workforce mobility, individuals are actively crafting pathways to secure their futures in a world that is increasingly unpredictable. Governments, in turn, are leveraging these dynamics to attract investment, talent, and innovation. As migration policies continue to adapt to the realities of a borderless economy, the concept of citizenship will further transition from a static identity into an evolving, customizable tool, one that empowers individuals to navigate a complex global order while ensuring resilience, security, and new opportunities for growth.