World Refugee Day is an international day established by the United Nations to honor refugees around the globe. This day is marked globally through a range of commemorative events and initiatives aimed at expressing solidarity with refugees and acknowledging the resilience and bravery of individuals compelled to leave their countries of origin, especially due to conflict or persecution1.

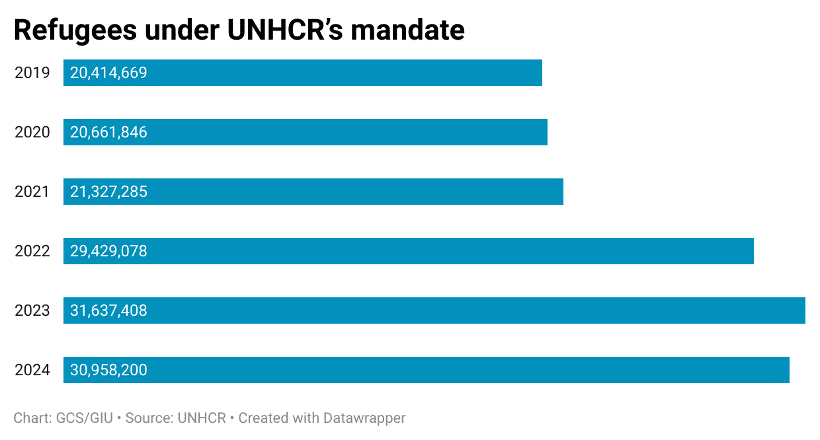

Currently, there is a growing trend in forced displacement. As of 2025((UNHCR. “Global Trends”, 2025, https://www.unhcr.org/global-trends, there are 123.2 million forcibly displaced people, including 42.7 million refugees and 73.5 million internally displaced persons (IDPs). In addition, approximately 4.4 million stateless individuals remain without legal nationality, and around 8.4 million people are seeking international protection under other categories.

The term “refugee” was formally defined in the aftermath of the Second World War through the 1951 Refugee Convention. A refugee, according to the Convention” is someone who is unable or unwilling to return to their country of origin owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion2.”

Under the UNHCR mandate3 refugees can receive international protection and be safeguarded when a person’s home country cannot or will not protect them from serious harm such as persecution, conflict, or violence. This protection ensures access to asylum, prevents forced return (non-refoulement), and upholds basic rights and dignity. Refugees are one of the primary groups who receive international protection, but others, such as asylum seekers and stateless persons, may also qualify. However, unfortunately, refugees often endure severe human rights violations and traumatic experiences during flights. Children are often victims of armed violence, trafficking, and prolonged detention4, violating the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), which guarantees protection from violence, exploitation, and the right to education and family life. Women and girls are exposed to gender-based violence5, including sexual assault and forced marriage, in violation of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), etc.

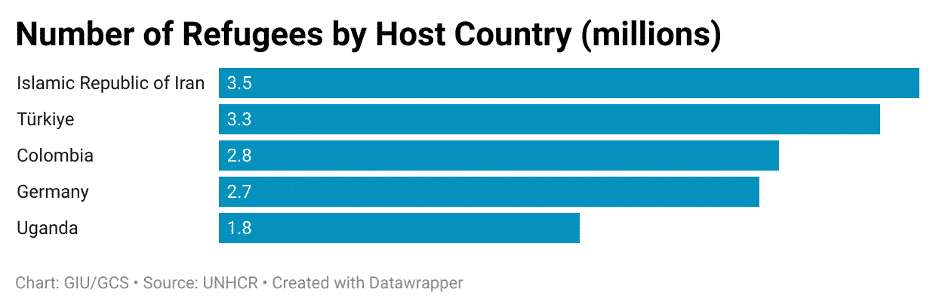

Refugee flows tend to concentrate in a limited number of host countries within a relatively short timeframe, placing substantial pressure on local infrastructure, public services, and humanitarian resources. Thus, receiving states often face immediate logistical and financial challenges6.

69% of refugees come from the following five countries:

Refugees are part of global migration patterns, and migration can be driven by various factors, including political instability, environmental changes, economic opportunities, etc.

Migration is mainly categorized as either voluntary or forced. Voluntary migration typically involves a personal decision, even when influenced by economic necessity. It includes movements for improved employment prospects, education, family reunification, lifestyle preferences, or through legal pathways such as investment migration. Conversely, forced migration occurs when individuals are compelled to leave their homes due to threats beyond their control. This includes refugees escaping persecution or armed conflict, internally displaced persons within their own countries, victims of human trafficking, or those affected by environmental factors.

Other common classification factors, that involve more detailed understanding can be according to the primary motivating factors, such as economic, humanitarian, or environmental causes.

However, Bakewell7 challenges the common definitions of forced and voluntary migration: What distinguishes voluntary from forced migration? The question defies simple answers. A person fleeing violence, abandoning all possessions, is typically deemed a refugee; a clear case of forced migration. Yet, upon gaining asylum and new citizenship, their subsequent relocation may appear voluntary. Consider a refugee who, after securing asylum, moves again seeking safer or better conditions: is this choice freely made? The line blurs further when we examine “voluntary” migration. Can migration driven by desperate circumstances – say, a graduate emigrating due to a lack of job prospects in her field, truly be called voluntary, even if it seeks a better quality of life? These complexities, supported by scholarly insights, reveal that the distinction between forced and voluntary migration is often ambiguous, shaped by timing, context, and perspective, challenging their analytical utility. Thus, migration trajectories often defy rigid categorization, demanding a nuanced understanding of human mobility.

Thus, by recognizing the variations and fluidity of migration experiences, states can better address the needs of refugees and stateless persons, ensuring policies reflect their complex realities rather than bureaucratic labels.

When addressing the topic of refugees, it is also fundamental to discuss the concept of statelessness. While not all refugees are stateless, many lack legal recognition by any state, leaving them without formal nationality.

Statelessness refers to the absence of a legal bond between an individual and a state, thereby denying access to fundamental rights typically guaranteed through citizenship. Without nationality, individuals are deprived of essential civil, political, and socio-economic rights, including the right to work, access healthcare and education, participate in political life, and claim social protection((Ahmad, Nafees. “The Right to Nationality and the Reduction of Statelessness – The Responses of the International Migration Law Framework.” Groningen Journal of International Law, vol. 5, no. 1, 2017, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3054456. Moreover, the absence of nationality severely restricts their freedom of movement, as they are often unable to obtain identification or travel documents or legally reside in any country. As a result, stateless persons are particularly vulnerable to prolonged and arbitrary immigration detention, often without access to legal rights. It is especially risky for individuals in detention settings, where statelessness is often unacknowledged due to gaps in legal frameworks and a range of interrelated objective, subjective, and structural barriers8.

Statelessness arises from various causes, including discriminatory nationality laws that exclude specific ethnic or religious groups (e.g., Rohingya in Myanmar9, Dominicans of Haitian descent10), state succession or dissolution where legal gaps leave people without nationality (e.g., post-Soviet and post-Yugoslav contexts), and conflicts or gaps in nationality laws, particularly affecting children of stateless or mixed-nationality parents. Other causes include gender-discriminatory laws preventing women from passing on nationality (e.g., in Lebanon11 and Kuwait), deprivation of nationality for political or security reasons (e.g., Bahrain or ISIS-linked cases), and lack of birth registration, especially among marginalized groups or in conflict zones12. The 1954 Convention Relating to the Status of Stateless Persons13 and the 1961 Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness14, ratified by 98 countries as of 2025, aim to protect stateless individuals and prevent new cases.

According to current UNHCR estimates, as of the end of 2023, at least 4.4 million individuals globally are known to be stateless, though the actual figure is likely significantly higher due to widespread underreporting and the often-hidden nature of stateless populations. Importantly, statelessness is frequently intertwined with displacement as a substantial number of stateless individuals have experienced forced displacement. For example, over 1.3 million stateless persons are currently counted among the world’s forcibly displaced populations15.

While statelessness remains a global issue, several countries have adopted strong preventive measures. Spain16 provides stateless individuals with access to social services, employment, and citizenship pathways for children born on its territory. Portugal stands out for protecting against childhood statelessness by granting citizenship to stateless children born in the country and facilitating access to nationality. In Latin America, Uruguay guarantees citizenship to all children born on its soil17, and Brazil18 was the first in the region to establish a statelessness determination procedure with legal residence and naturalization routes. In Asia, the Philippines has shown leadership by ratifying key treaties and promoting birth registration among marginalized populations. These examples illustrate effective models for reducing and preventing statelessness globally.

As displayed above, while stateless, people are deprived of basic human rights and necessities. Citizenship functions as a gateway to the exercise of one’s rights, serving as the legal basis for an individual’s inclusion within a political and social community. As Hannah Arendt famously argued, the stateless are deprived of the very “right to have rights,” as they lack a recognized place in the international order where their voices carry weight and their actions hold significance. Without legal nationality, individuals are effectively excluded from the frameworks that confer agency, protection, and participation in public life19.

Citizenship is a foundational mechanism through which individuals attain a dignified existence. It grants access to a broad spectrum of civil, political, and socio-economic rights, including education, healthcare, legal protection, and political participation, all of which are vital for individual well-being and societal inclusion.

While traditional pathways to citizenship typically involve birth, descent, or naturalization, alternative mechanisms such as investment migration can be another option of obtaining citizenship. For example, in 2020 Vanuatu announced its intention to extend its Citizenship-by-Investment (CBI) program explicitly to stateless individuals20, providing a legal identity in exchange for economic contribution. However, such initiatives remain rare and largely inaccessible to most stateless or forcibly displaced persons, who often lack the financial means to qualify for these programs.

This article addressed key issues surrounding refugees, statelessness, and the importance of legal identity. It explored the definitions and protections available to refugees, the challenges they face during displacement and integration, and the often-overlooked problem of statelessness. It also highlighted how some countries are leading by example in preventing and reducing statelessness through inclusive laws and procedures.

At the heart of these issues lies citizenship, which enables access to civil, socio-economic, and political rights, and represents the institutional recognition of individuals within international order. Without it, people are denied the basic protections and participation that form the foundation of a dignified life. As it was highlighted in the article, migration is not a rigid or uniform experience. To respond effectively, states must acknowledge the complexity and diversity of migration journeys and adopt flexible, inclusive policies that ensure no one is left without a place to belong.

On this International Refugee Day, the urgent realities faced by refugees and stateless persons underscore the significance of legal belonging. Thus, citizenship serves as not only a legal safeguard but a prerequisite for human dignity and full participation in society.