Digital nomadism has moved from fringe experiment to mainstream mobility strategy. What began in the late 1990s as a laptop-enabled niche was propelled into the global spotlight by the pandemic, when remote work became a default rather than a perk. As firms normalized distributed teams and cloud collaboration, millions discovered they could choose whereto live without changing what they do. Governments followed suit: since 2020, dozens of jurisdictions have launched purpose-built visas and residency routes to attract this mobile, high-spending, low-dependency population.

The Global Digital Nomad Report 2025 maps this shift with a comparative, data-driven lens. We analyze 64 countriesacross six dimensions—Procedure, Citizenship & Mobility, Tax Optimization, Economics, Quality of Life, and Tech & Innovation—built from 15 normalized indicators. Our approach blends official sources with respected public datasets, weights them by real decision drivers (internet speed, visa clarity, costs, tax treatment, innovation capacity, English proficiency), and produces a transparent overall score plus sub-index rankings. The result is a clear picture of where digital nomads can thrive—and why.

This year’s edition goes beyond “where can I go?” to “what long-term value does a place offer?” We track the surge of post-2020 visa programs, the dominance of one-year renewable models, the split between worldwide and territorial tax systems (including special regimes for newcomers), and the rising importance of fast connectivity and innovative ecosystems. We also examine long-horizon pathways—permanent residency and, in a handful of cases, citizenship—that convert temporary stays into durable mobility advantages. Regionally, Europe leads on structured routes and quality of life; the Americas balance affordability and openness; Asia offers world-class tech with tighter eligibility; Africa presents cost-effective options constrained by infrastructure; and the Gulf provides speed and tax clarity without permanence.

Finally, this report is written for three audiences. For nomads, it is a practical playbook to match personal goals with visa rules, costs, and lifestyle trade-offs. For policymakers, it is a benchmarking tool to upgrade programs—from minimum-viable visas to frameworks that foster talent, startups, and regional development. For cities and communities, it is a guide to convert arrivals into embedded value through broadband, housing supply, coworking capacity, and integration initiatives. Above all, the report aims to inform—and de-risk—choices on both sides of the border so that flexible work translates into shared, long-term prosperity.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, digital nomadism was primarily conceptualised as a niche lifestyle pursued by a relatively homogenous group, predominantly freelance professionals in technology, design, marketing, and other location-independent sectors. Early research, such as Reichenberger (2018), portrayed these individuals as self-employed, highly mobile workers who leveraged digital tools to combine travel with income generation.1 Previous to the pandemic, only about 7 percent of U.S. workers worked, in July 2020, 42 percent of American workers reported working from home full-time.2 That global shift was not temporary. Instead, it cemented remote work as a fixture of modern employment. By 2025, in the United States, about 22% of the workforce continues to work remotely, representing 32.6 million Americans. This is particularly relevant because remote work, supported by technology and global mobility, is one of the primary enablers of digital nomadism.

As Kaisu Koskela (2022) notes, the pandemic removed much of the perceived risk of remote arrangements for both employees and employers, embedding flexible work policies into mainstream business practice.3 This change catalysed a diversification of the digital nomad demographic: full-time employees, who were once marginal in nomadism research, in 2020 accounted for approximately 40% of the global nomad community.4 Contractors and hybrid professionals have also gained prominence, blurring the boundaries between traditional employment and self-directed work.

Technology remains the structural backbone of this lifestyle, but its role has expanded. The dominance of tech-related professions (software development, SaaS entrepreneurship, digital marketing) reflects what Thompson (2018) describes as the “location-independent work paradigm.”5 Koskela’s framing situates digital nomadism as a manifestation of the digital economy’s spatial flexibility, where production is no longer tethered to a specific geography.3 In this sense, digital nomads are not simply travellers with laptops; they are active participants in a globalised knowledge economy, facilitated by high-speed internet, cloud-based collaboration tools, and platform-mediated labour markets.

However, access to this mobility is far from equal. The “passport power divide” significantly shapes who can participate. Nationals from high-mobility countries (predominantly in the Global North) enjoy visa-free or visa-on-arrival access to a wide range of destinations, allowing them to maintain fluid work-travel cycles. Koskela warns that while digital nomadism is marketed as universally attainable, it is in reality easier for those with privileged citizenships, a phenomenon she calls “privilege mobility.”3 Cohen, Duncan, and Thulemark (2015) similarly highlight the importance of mobility capital, which encompasses legal rights, financial resources, and cultural competencies that sustain long-term travel and work abroad.6

A related evolution in post-pandemic nomadism is the rise of “slomadism”,7 extended stays of several months or more in a single location. This slower pace not only offers deeper cultural immersion but can also be strategically aligned with long-term residency and citizenship goals.8 Ho and Bauder’s (2020) concept of “strategic citizenship” captures this trend, wherein individuals intentionally accumulate residence time in jurisdictions with favourable naturalisation laws. Koskela observes that residency-by-investment schemes, long-stay visas, and nomad-specific permits are increasingly part of nomads’ strategic planning, blurring the line between lifestyle mobility and migration policy navigation.3

The economic potential of digital nomadism is equally noteworthy. Data showing that 79% of nomads earn over USD 50,000 annually positions them as a lucrative demographic for host countries.9 Germann Molz (2011) conceptualises nomads as “mobile micro-economies,” whose spending on accommodation, coworking, dining, and leisure stimulates local markets.10 Koskela reinforces this view, noting that governments see nomad visas as a way to attract high-spending, low-dependency residents who contribute economically without straining public resources.3 This has led to a proliferation of nomad visa schemes globally, from the Caribbean to Eastern Europe, tailored to attract this segment. In the GDNR 2025, we present a comprehensive analysis of these schemes and rank the top destinations for digital nomads, both overall and across six key dimensions.

Digital nomadism refers to the lifestyle of individuals who use technology to work remotely while relocating between destinations across the globe. Once considered a fringe phenomenon, the lifestyle gained significant momentum after the COVID-19 pandemic, when remote work became both normalized and widely accessible. What had previously seemed exceptional suddenly became feasible for millions, and digital nomadism emerged as a mainstream aspiration. Today, digital nomads can be freelancers, entrepreneurs, employees, or even aspirants experimenting with blending work and travel in flexible ways.

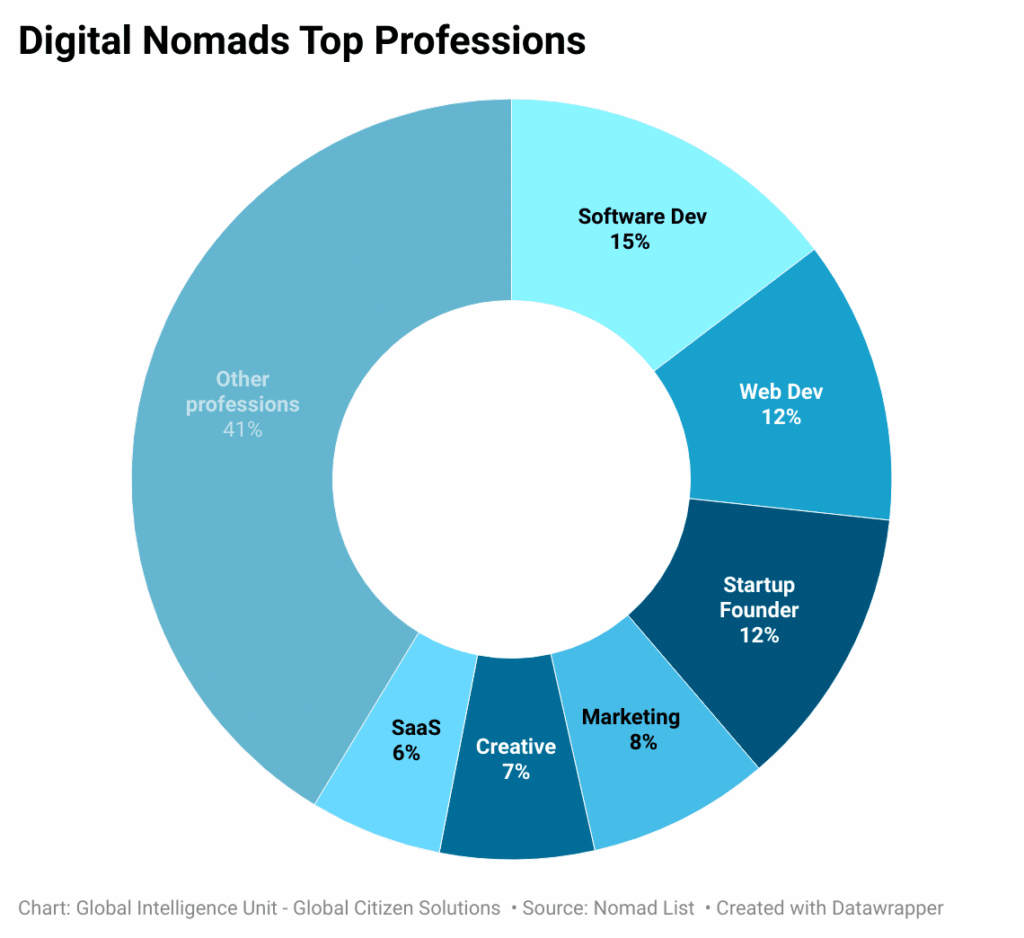

Freelancers represent the most traditional image of the digital nomad, offering services such as software and web development, marketing, creative design, and communication work. Pre-pandemic studies largely focused on this group, highlighting its role in knowledge-based industries. Yet, alongside freelancers, there exists a smaller but influential group of business owners who run registered companies with employees, contractors, and sometimes physical product inventories. These entrepreneurs, often startup founders, make up about 12,25 percent of the community and occupy a unique space where independence overlaps with organizational leadership.9

In the United States, the number of digital nomads shifted dramatically during the pandemic. In 2019, independent workers accounted for 4.1 million (56.2%), while traditional job holders made up 3.2 million (43.8%). By 2020, the balance had flipped: independent workers rose modestly to 4.6 million (42.2%), but traditional employees surged to 6.3 million (57.8%)4, overtaking freelancers as most digital nomads. This change underscores how the pandemic rapidly expanded who could adopt the lifestyle.

It is generally much easier for digital nomads who do not cross international borders to remain employees, as domestic nomadism eliminates many fiscal, immigration, and regulatory risks. However, once traditional employees begin working nomadically across borders, they may expose their employers to tax, compliance, and legal challenges. Despite these risks, few organizations have formal policies addressing digital nomadism. Many employees operate under informal or “don’t ask, don’t tell” arrangements with their managers, while others travel without their organization’s knowledge, effectively placing themselves off the grid, both literally and figuratively. This diversification of roles reflects not only broader changes in work but also a growing acceptance by companies of distributed teams and flexible policies.11

Alongside these established groups, there are also experimental nomads (individuals testing the lifestyle without yet having stable income streams) and so-called armchair nomads, who plan to adopt the lifestyle in the future.12 Their presence in coworking spaces, online communities, and planning stages suggests that millions are considering joining the nomadic wave, reinforcing its mainstream appeal.

Despite this diversity, technology-related professions dominate the landscape. Data shows that software and web developers together represent more than a quarter of the nomad workforce, while startup founders add another significant share. Other highly visible professions include marketing, creative industries, SaaS, UI/UX design, product management, finance, data analysis, and emerging fields such as crypto (see chart below). Altogether, these figures highlight the central role of technology and digital infrastructure in enabling this lifestyle. It is not merely that these fields allow location-independent work, but also that they actively shape the identity and global distribution of the digital nomad community.

Mobility remains the defining element of digital nomadism. Typically, individuals can relocate guided by visa opportunities, tax advantages, or lifestyle benefits. For many, the distinction between domestic and international travel is less important than the fundamental detachment from a permanent home base. However, in this Report, we focus on international digital nomdism the core of our analysis is the regulations states adopt in their immigraton framework to attract digital nomads.

The demographics of digital nomads reveal a distinct profile. According to recent data from Nomad List, men represent around 79 percent of the community while women are 21 per cent, this has grown by 3% from 2024 to 2025.13

Nearly all belong to the Millennial or Gen Z cohorts, illustrating the lifestyle’s popularity among younger generations. Nationally, the United States accounts for 43 percent of all digital nomads, while only two developing countries (Russia and Brazil) make the global top ten.13 Financially, this is an affluent group. Nearly four out of five earn more than $50,000 annually, while a small but striking 2 percent earn over $1 million, the average annual salary of digital nomads being in 2025 is $124,416.13 With Millennials and Generation Z expected to inherit $84 trillion over the coming decade, this wealth transfer is likely to accelerate the sophistication of the digital nomad economy.14 Services, infrastructure, and technological solutions catering to mobile professionals will expand as providers recognize the purchasing power and expectations of this globally distributed market.})

Yet the lifestyle is not equally accessible to everyone. A strong passport is often the most valuable asset a digital nomad can hold. Citizens of countries such as the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, Germany, and the Netherlands dominate the global distribution, together accounting for 68 percent of nomads in 2025.13 Their high-ranking passports, as measured by the Global Citizen Solutions Passport Index15, allow for easier visa-free or visa-on-arrival travel. By contrast, individuals from weaker-passport countries frequently work remotely for companies based in wealthier nations but remain physically constrained in their mobility. For many of them, digital nomadism becomes a strategic pathway to second citizenship, enabling enhanced travel freedom and access to new markets.

Within this context, the phenomenon of “slomadism” has gained traction. Slomads prefer extended stays, often lasting several months, and sometimes transition toward residency or even citizenship in their host countries.16 These extended relocations are frequently strategic, designed to take advantage of pathways to stronger passports and enhanced long-term mobility.

Ultimately, digital nomadism is more than a lifestyle, it has become a global mobility strategy. For individuals, it enables career flexibility, geographic choice, and opportunities to optimize both work and personal lives. For host nations, it represents an opportunity to attract skilled and high-earning residents, while also presenting challenges in terms of visa regulation, taxation, and infrastructure. As technology and wealth continue to converge with mobility, the digital nomad phenomenon is poised to expand further, reshaping how we think about work, travel, and citizenship in the twenty-first century.

With 64 countries now offering nomad or remote-worker visas, governments are actively competing for globally mobile earners. Unlike mass tourism, nomads typically stay longer, spend on services, and embed in work-oriented networks. Coworking hubs often function as micro-clusters that diffuse knowledge and seed entrepreneurship, but without clear tax, labor, and residency frameworks many nomads operate informally, blunting local gains and raising compliance risks. As traditional corporate FDI remains weak, nomads constitute an FDI-adjacent channel of human and financial capital, especially where visas move beyond pandemic-era “MVPs” to include founders, pathways to residence and citizenship, geographic diversification beyond saturated cities, and investments in broadband, coworking, and housing.17

Research on Chiang Mai, Thailand, shows that long-stay nomads generate steady demand for cafés, coworking spaces, and apartments, while also organizing meetups and sharing expertise that link locals to global contracts.18 At the same time, scholars caution that inflows of nomads can trigger rising housing costs, gentrification, and cultural frictions, particularly when they concentrate in already popular districts.19 This duality reflects a broader misunderstanding: digital nomadism is often conflated with mass tourism, when in fact nomads tend to stay longer, spend differently, and engage in work-oriented networks.20 While overtourism strains local resources by concentrating visitors in short bursts, digital nomads can provide stable, year-round demand, if policies are designed to integrate them rather than treat them as temporary tourists.

As Ana Maria Kochanska (The Remote Impact) argues, the most durable benefits come from knowledge exchange, local innovation, and new business creation that embed value within host economies, outcomes that require frameworks for integration, not ad-hoc arrangements.21 Coworking hubs are a good example: studies show they operate as micro-clusters that diffuse know-how, attract entrepreneurs, and bridge nomads with local firms.22 But where tax, labor, and residency rules are unclear, many nomads remain “off the grid,” sometimes working without explicit employer approval. This informality blunts local gains and raises compliance risks for companies and governments alike.

These dynamics matter even more against a weak global investment backdrop. In national accounts, nomad spending is logged as tourism services, not foreign direct investment (FDI), but strategically many governments now treat nomads as FDI-adjacent actors: carriers of foreign income, human capital, and entrepreneurial intent.

The markets most visibly shaped by digital nomadism already reveal substantial scale and momentum. The coworking sector alone was valued at nearly $15 billion in 2024, with forecasts placing it between $40–46 billion by the end of the decade, signaling a steady mid-double-digit growth trajectory. Within the broader flexible office market, projections point to expansion from about $45 billion in 2025 to more than $136 billion by 2032, reinforcing JLL’s long-standing estimate that around 30% of global office space could be flexible by 2030—a structural rather than cyclical shift.23 Supply growth is equally evident: by 2024, there were close to 42,000 coworking spaces worldwide, with the U.S. accounting for nearly 7,800 sites and 140 million sq ft of flexible stock.24

Parallel dynamics are visible in co-living, a market sized at roughly $8 billion in 2024 and expected to double by 2030, with some estimates projecting even faster growth.25 In the UK, development pipelines confirm investor conviction, with planned and approved units nearly doubling year-on-year in 2024.26 Together, these figures highlight how digital nomadism intersects with real estate innovation, driving demand for hybrid work and living infrastructures that blend flexibility, scale, and long-term investment potential.

Spillovers extend beyond real estate. Extended-stay hotels and aparthotels are expanding on the back of longer residencies27, travel eSIMs and connectivity tools are scaling with distributed work28 and cross-border payments and fintech are growing as professionals earn in one jurisdiction and spend in another.29 Additionally, relocation and visa services are professionalizing a once-informal layer of mobility. Each of these markets converts longer stays into steadier, year-round demand and lowers the friction for new firm formation.

A further dimension to consider is most digital nomad visas today are not limited to salaried remote workers; they also extend eligibility to startup founders and business owners, making them a strategic channel for countries to attract new businesses and entrepreneurial talent. This design transforms digital nomadism from a temporary mobility trend into a potential pipeline for foreign direct investment and firm creation. For instance, Portugal’s D8 Digital Nomad Visa and Spain’s program under the Startup Act both allow entrepreneurs to settle, operate their companies, and transition to permanent residency within five years. Italy and Greece follow similar models, granting pathways to citizenship after long-term residence, while countries such as Brazil and Uruguay include business owners in their nomad frameworks, leading to permanent residency within three to five years. By integrating nomad visas with startup-friendly provisions, states effectively use these schemes as tools to stimulate local innovation ecosystems, attract high-value business formation, and diversify investment inflows beyond traditional corporate FDI.

In sum, the conflation of digital nomads with overtourism risks undermining sound policy. As mentioned, tourists typically stay days or weeks; nomads often stay months, spend on services rather than short-term leisure, and become semi-integrated into communities. Yet when they cluster in already saturated urban centres, their presence can intensify housing shortages and fuel narratives that digital nomadism is simply “tourism by another name.” Without proper communication and local engagement, this misunderstanding can erode community support. Clear distinctions (between tourism and long-stay residency) are critical to reframing digital nomads as potential partners in development rather than burdens on local infrastructure.

The challenge for states is how to attract international talent without generating conflict with local communities. Several strategies are emerging:

- Geographic diversification: Encouraging digital nomads to settle in underdeveloped or peripheral regions—rather than concentrating in capital cities—can distribute economic benefits more evenly. Countries such as Spain and Portugal have piloted incentives to direct nomads to rural or inland towns, aligning with broader regional development goals.

- Infrastructure and housing supply: Expanding broadband coverage, investing in coworking spaces, and supporting affordable housing construction can ensure that nomads enhance rather than strain local capacity.

- Community integration: Programs that connect nomads with local entrepreneurs, universities, and civic projects reduce cultural distance and increase the chances of knowledge spillovers.

- Clarity on regulation: Transparent tax, residency, and labor guidelines reduce compliance risks for both employers and workers, transforming informal practices into structured opportunities.

As Kochanska observes, many digital nomad visas were rolled out hastily during the pandemic as “minimum viable products,” aimed at capturing the trend without long-term foresight. To ensure their durability, she argues that governments must move beyond short-term fixes and develop frameworks that are streamlined and flexible, while also incorporating clear pathways to residency, business integration, and structured community participation, measures that can transform digital nomadism from a transient tourism model into a driver of sustainable development.30

Ultimately, digital nomadism highlights the convergence of remote work, mobility, and global investment flows. For states, the goal is not just to attract nomads but to harness their presence for regional development, particularly in underdeveloped areas that can benefit from an influx of talent and spending. If implemented with foresight, digital nomadism can complement traditional FDI by creating new micro-ecosystems of innovation and stability. But to succeed, policymakers must balance attraction with protection, ensuring that local communities see tangible benefits and that mobility becomes a driver of shared prosperity rather than division.

As we introduce the Best Countries for Digital Nomads in the second edition of the Global Digital Nomad Report (GDNR) we analyse 64 jurisdictions compiling it into a clear, comparable index. Building on our 2024 baseline, we refined the definition of digital nomadism and assessed each country across 15 indicators grouped into six dimensions: Procedure, Citizenship & Mobility, Tax Optimisation, Economics, Quality of Life, and Tech & Innovation. Finally, we weighted by relevance to nomads’ real decision drivers, drawing on academic research, expert input, and client insights.

We intend the GDNR to serve as a practical guide for individuals choosing where to live and work, a reference for governments designing smarter regulations, and a resource for media explaining the phenomenon, ultimately helping all stakeholders understand it better and derive value from it.

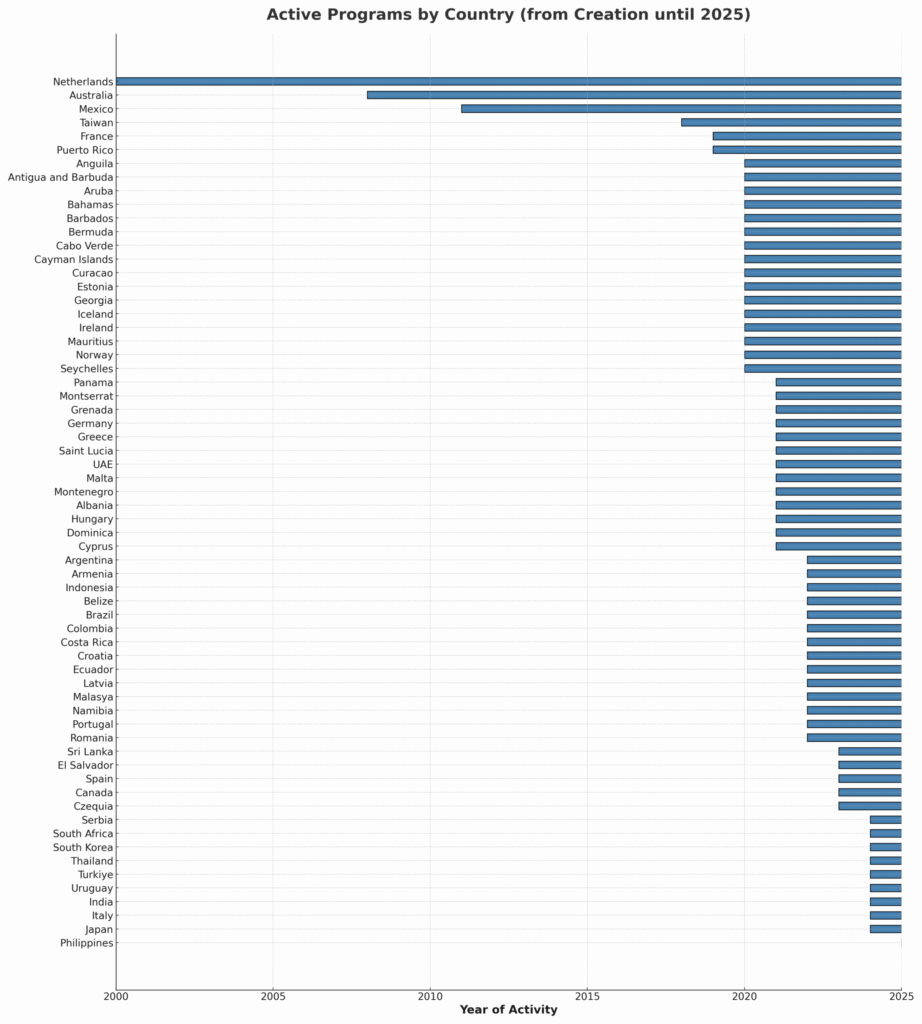

Digital Nomad Visas (DNVs) are immigration policies introduced by many countries, mostly after the pandemic, as remote work became widespread across the globe. In fact, 58 out of the 64 programs (over 90%) were created after 2020, reflecting how countries rapidly adapted to attract mobile professionals as part of their post-pandemic recovery strategies. This surge highlights both the rising demand for location-independent lifestyles and governments’ recognition of digital nomads as a source of economic diversification. The chart below illustrates the global spread of digital nomad visa programs, showing the year of creation for each country and their continuity until 2025. A clear pattern emerges: while early adopters like the Netherlands (2000) and Australia (2008) pioneered the concept adopting fexible immigration legislation for freelancers, the vast majority of programs were launched in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, when remote work became mainstream.

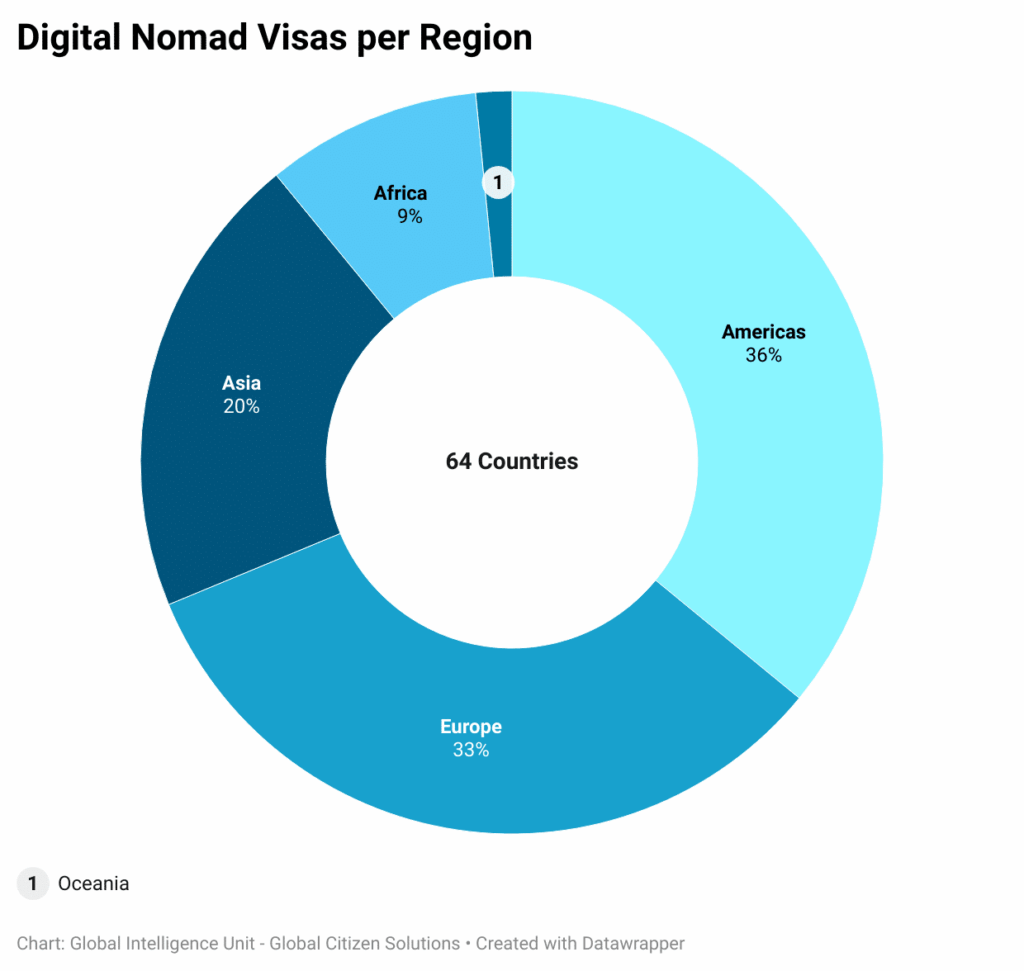

Regionally, digital nomad programs reflect different priorities and strengths, each with distinct advantages and challenges. Europe, with 21 programs (33%), stands out for its structured frameworks in countries such as Spain (1st), Portugal (6th), Malta(10th), and Germany (8th), where visas grant access to Schengen zone and are often tied to permanent residency or citizenship, making the region highly attractive for long-term relocation. Its main challenge lies in relatively high living costs and worldwide taxation, which can reduce its appeal for cost-sensitive freelancers. Eastern Europe is rapidly emerging as a compelling hub for digital nomads, thanks to its combination of affordability, cultural richness, and increasingly favorable visa frameworks. Countries such as Estonia(32nd), Croatia(28th), Czechia (5th), Romania (13th), Latvia (21st), and Hungary(16th) now offer dedicated digital nomad visas. These programs typically grant one-year residence with extension options, and some (like Czechia) even provide pathways toward permanent residency or citizenship for eligible applicants. What makes Eastern Europe especially attractive is its high quality of life at a moderate cost of living, robust internet infrastructure, and proximity to both Western Europe and broader Eurasian regions.

The Americas, home to 23 programs (36%) and early adopters like Barbados(52nd) and Bermuda(42nd), emphasize lifestyle benefits, favorable climates, and tax-free regimes, making them ideal for wealthier nomads seeking flexibility; however, their short-term focus and lack of settlement pathways limit opportunities for those wanting permanence. Colombia(31st), Brazil(15th), Ecuador(11th), El Salvador(34th), and Uruguay (3rd) have all introduced DNVs, typically offering one- to two-year residency with renewal options and path to permanent residency and citizenship with reduced time for naturalization.

Asia, with 13 programs (20%), is a more recent entrant, highlighted by selective launches in Japan (33rd), South Korea(29th), Thailand(44th), and the Philippines(26th), often targeting specific nationalities or tech professionals; while the region boasts excellent infrastructure and some of the world’s fastest internet speeds, its restrictive eligibility rules and high income requirements create barriers to access.

Africa, though smaller with six programs (9%), offers some of the most affordable entry points through countries like Mauritius(49th), Cabo Verde(56th), and Namibia(23rd), appealing to budget-conscious nomads, but weaker infrastructure and slower internet speeds remain significant obstacles.

Finally, Oceania, represented solely by Australia(39th), provides flexibility through established schemes like the Work and Holiday Visa, though stringent eligibility and higher living costs restrict its accessibility. Together, these regional differences reveal a global landscape split between Europe’s long-term migration pathways, the Americas’ tax-driven short stays, Asia’s selective high-tech hubs, and Africa’s affordable but infrastructure-limited opportunities.

Procedure

Visa duration and extensions

The analysis of visa durations shows that the 1-year digital nomad visa is the global standard, accounting for nearly two-thirds of all programs (about 66%). Out of the 64 countries offering DNVs, the vast majority (76.6%) allow extensions or renewals, signaling a global policy trend toward flexibility, while a smaller group (23.4%) maintain stricter, non-renewable terms.

The global landscape of digital nomad visas reveals striking differences in duration and renewability, two critical factors for professionals planning long-term remote living abroad. At the top tier are programs offering multi-year stays with extension options, which provide the greatest flexibility and stability. Taiwan leads the pack with a 3-year visa that is also extendable, making it the strongest long-horizon option worldwide. Close behind are the 2-year extendable visas of countries such as Colombia, Ecuador, El Salvador, Norway, the Cayman Islands, and Montenegro, which balance generous entry durations with the possibility of renewal. These options position such destinations as particularly attractive for digital nomads seeking to establish a stable base while retaining long-term mobility.

A second strong category includes the 1-year renewable visas, which dominate in terms of availability across regions. In Europe, countries like Portugal, Spain, Italy, Malta, Romania, Serbia, Greece, Latvia, Cyprus, and the Netherlandshave adopted this model, making the continent one of the most flexible hubs for nomads. In the Americas and the Caribbean, the same pattern emerges in Mexico, Costa Rica, Panama, the Bahamas, Bermuda, Saint Lucia, Grenada, and Dominica (the latter offering 1.5 years initially). Across the Asia-Pacific, countries such as Indonesia, Malaysia, South Korea, the Philippines, and Sri Lanka offer renewable options, while in Africa, Mauritius, Seychelles, and South Africa provide steady one-year pathways with renewability. Together, these programs illustrate how many regions use the renewable one-year model as a policy sweet spot to attract talent while maintaining regulatory oversight.

Not all destinations, however, are equally suited for long-term stays. Some countries restrict their digital nomad visas to short, non-renewable periods, limiting the appeal for professionals seeking stability. For instance, Thailand, Japan and Iceland impose short terms with no extension possibilities. Similarly, the UAE and countries such as Croatia, Estonia, Georgia, and India offer only 1-year non-renewable visas, meaning nomads must reapply or relocate after expiry. Interestingly, a few countries like Germany allow generous entry durations but do not permit renewals, offering a middle ground that favors medium-term but not indefinite stays.

When viewed regionally, clear patterns emerge. Europe offers the broadest long-term runway, with a wide range of renewable one-year programs complemented by Norway’s 2-year extendable visa and Germany’s 3-year non-renewable option. Latin America and the Caribbean stand out for multi-year extendable horizons, notably in Colombia, Ecuador, El Salvador, and the Cayman Islands, alongside widespread one-year renewable models. Asia-Pacific is mixed but hosts both the best long-term option globally (Taiwan’s 3-year renewable visa) and several other reliable one-year renewables. Africa maintains steady options through Mauritius, Seychelles, and South Africa, while the Middle East is more limited, with the UAE being an example of a short-term, non-renewable system.

On the other hand, Anthropologist Kaisu Koskela observes that many digital nomads follow a strategy of short-term stays across multiple countries, making long-stay visa regulations poorly aligned with their mobility patterns. Koskela argues that many digital nomads bypass DNVs because the products rarely fit the way nomads actually move.31 DNVs anchor people to one country for long periods, while many nomads rotate every few weeks or months; if short-stay entry already lets them live and work as they do, they see little reason to add paperwork and fees. She also points to design frictions, high or ill-matched income thresholds, nationality/occupation filters, and uneven rollouts of pandemic-era “minimum viable” schemes, which create uncertainty and exclude large portions of the community. Finally, tax and social-security exposure for employers dampens take-up among salaried workers. In her view, today’s DNVs tend to suit remote professionals testing relocation more than “always-on-the-move” nomads, and they need clearer rules and better alignment with mobile work patterns to drive wider adoption.

Who can apply?

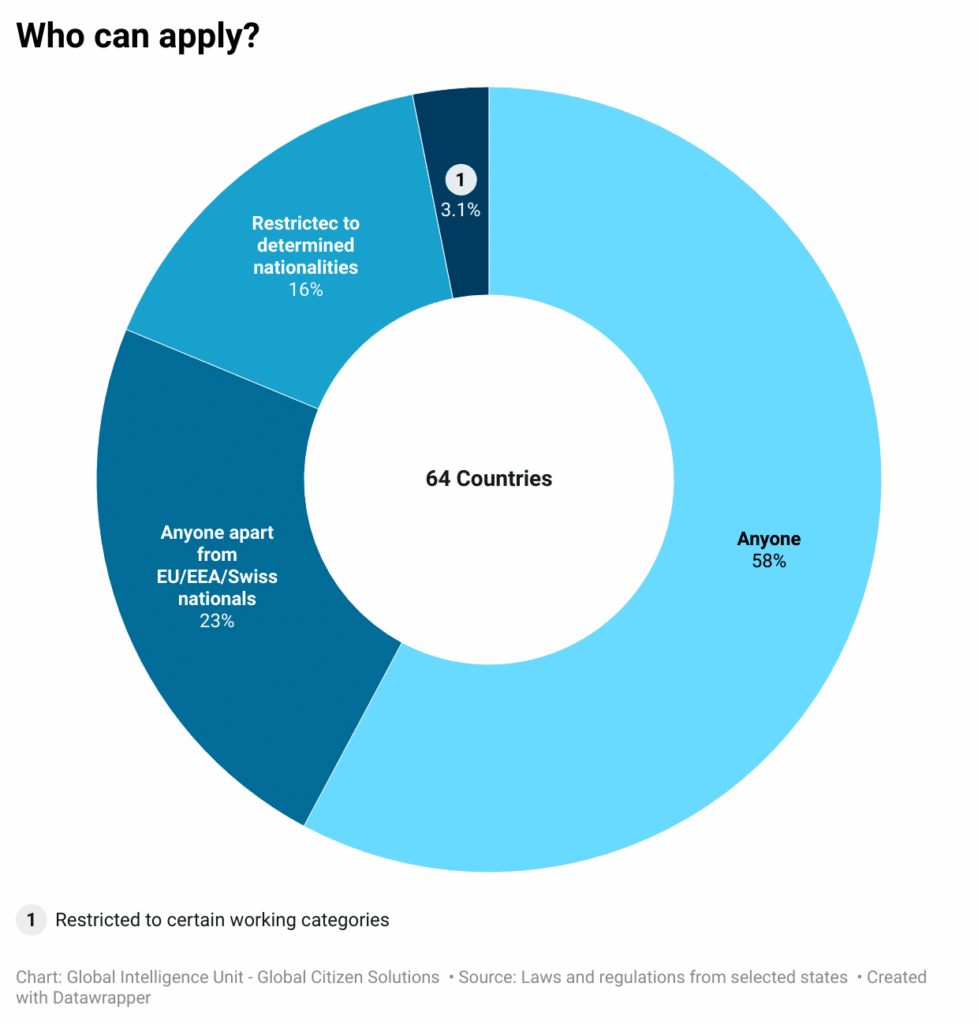

Across the 64 digital-nomad and remote-worker visas we track, eligibility is far more open than many assume. A clear majority (37 programmes, about 58%) are available to any nationality. Another 15 programmes (23%) are open to non-EU/EEA/Swiss nationals only, which mostly reflects Europe’s free-movement rules for its own citizens rather than an added barrier. A smaller group of 10 schemes (16%) restricts access to specific passports, and just two (3%) limit eligibility to particular professional categories related to tech and healthcare fields.

The regional pattern is telling. In the Americas and the Caribbean, most destinations (Antigua and Barbuda, Barbados, Bahamas, Bermuda, Cayman Islands, Dominica, Grenada, Mexico, Panama, Uruguay, and others) welcome “anyone,” mirroring their strategy to convert seasonal tourism into year-round, service-led demand. Europe often appears restrictive at first glance, but the common wording “anyone apart from EU/EEA/Swiss nationals” simply acknowledges that EU/EEA citizens already enjoy free movement; in practice, these visas target third-country professionals. Asia is mixed: India, Indonesia, Thailand, and the Philippines are broadly open, while Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, and Türkiye limit access by nationality. In Africa and the Middle East, policies range from fully open (UAE, South Africa, Namibia, Seychelles) to nationality-limited frameworks (Cabo Verde, Mauritius). Outliers like Australia and Georgia are fully open and continue to draw strong interest.

Where restrictions exist, they tend to serve clear policy aims. Nationality-limited lists usually reflect bilateral relations, security vetting capacity, or a phased rollout. Category-limited schemes (seen in places like Germany and Malaysia) prioritise role fit (e.g., digital or creative professionals) over volume, aligning inflows with labour-market needs and the local innovation agenda.

Koskela highlights that many DNV programs impose significant restrictions based on nationality or professional category, which limits accessibility for many would-be nomads. These filters often steer selection toward individuals who already possess “mobility capital” (strong passports or specific high-skill roles).These restrictive filters often reflect policy designs oriented toward economic or demographic goals, but they misalign with the diverse, fluid ways people practice nomadism, and, in her view, risk reinforcing structural inequalities in access to mobility.

For policymakers, the design choice is a trade-off between reach and precision. Open-to-anyone regimes maximise the talent pool and are easier for employers and freelancers to navigate. Targeted lists can protect administrative bandwidth and sharpen the human-capital profile, but risk dampening deal flow and knowledge spillovers. The sweet spot many countries are moving toward is broad eligibility paired with clear guidance, transparent processing, and, crucially, founder-friendly pathways to residence. Done well, these programmes don’t just attract remote earners; they channel skills, spend, and entrepreneurship into local ecosystems, exactly the kind of FDI-adjacent value cities and regions are competing to capture.

Visa income requirements

Income floors in digital nomad visas are a powerful policy signal: they indicate the type of mobile professional a country wants to attract. At the upper end (>$50k–$100k+), these thresholds act as a filter for high-earning, globally mobile workers in sectors like tech, finance, and consulting. The UAE ($72k) exemplifies this strategy, framing its digital nomad visa as a premium product that aligns with the country’s high-cost, high-status positioning. Similarly, the Cayman Islands ($100k) clearly aim at affluent nomads who can sustain living costs in a jurisdiction already known for wealth density (Cayman Compass). Even Japan ($68k) shows that high income floors don’t automatically discourage digital nomads: it has successfully attracted mobile professionals by pairing strict entry requirements with its strong innovation ecosystem and lifestyle appeal.

That said, income floors do not determine success on their own. Many of the most dynamic nomad destinations sit in the mid-band ($25k–$45k), where thresholds balance accessibility with quality filtering. Italy, Greece, and Portugal all stand out as countries that have paired moderate income requirements with attractive tax regimes, high quality of life, and pathways to residency. These features, rather than the income floor itself, explain why they continue to draw thousands of digital nomads each year.

The key lesson is that income floors help frame the policy narrative (premium filters in wealthy hubs versus inclusive entry points in mid- and low-threshold countries) but they are not the decisive factor. What ultimately drives digital nomad flows is the overall package: quality of life, tax clarity, visa simplicity, quality of infrastructure, cost of living, and a credible pathway for staying longer. Governments aiming to turn short-stay nomads into contributors to local economies need to think beyond thresholds and focus on making their ecosystems attractive and sustainable.

Regarding visa application costs, digital nomad visa fees fall into clear tiers that mirror policy goals: a handful of countries keep costs free or symbolic to maximize accessibility (Georgia, Mauritius, South Africa, or Uruguay) while most sit in a moderate band that balances openness with admin cost recovery, such as Spain, Italy, Germany, Colombia, Brazil, and the UAE. A smaller group prices at a premium to signal selectivity and a higher-touch experience (examples include Portugal, Norway, the Bahamas, and Dominica) and a few outliers charge very high fees to screen for affluent applicants or manage limited capacity, notably Indonesia, Cayman Islands, Barbados, and El Salvador.

Citizenship and Mobility

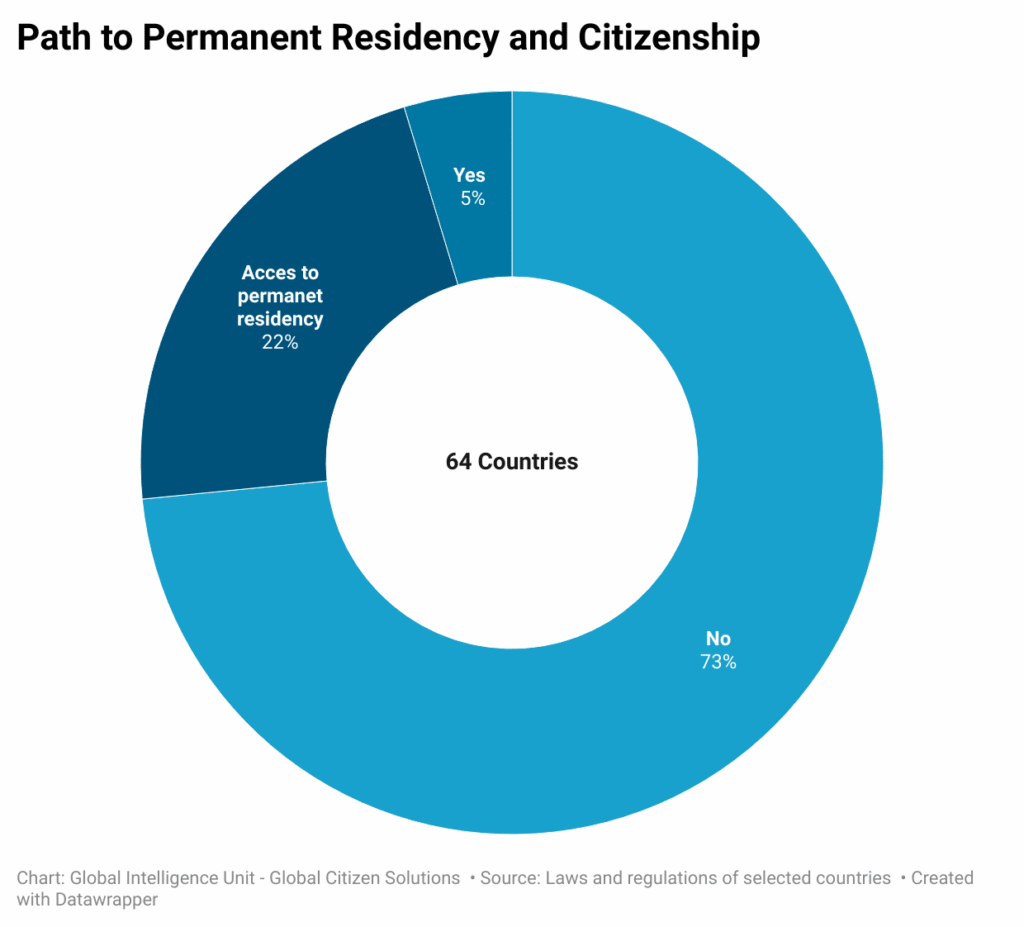

The proliferation of digital nomad visas since 2020 has transformed global mobility regimes, yet their legal architecture remains overwhelmingly temporary. Based on a dataset of 64 countries, only 3 cases (Czechia, Greece, and Spain) directly link the DNV to citizenship acquisition. A further 14 cases (21.9%), including Portugal, Italy, Germany, Netherlands, Norway, Canada, Brazil, Mexico, Ecuador, El Salvador, and Uruguay, allow transitions to permanent residency (PR), which in most legal systems functions as a prerequisite to naturalization. The remaining 47 programs (73.4%) terminate without conferring residency or citizenship rights, reflecting governments’ preference to harness short-term economic spillovers without extending full membership. This imbalance aligns with migration scholarship emphasizing the tension between states’ desire to attract mobile talent and their reluctance to dilute sovereignty through mass naturalization.32

Europe accounts for 24 of the 64 DNV jurisdictions, and it offers the most favorable conditions for long-term integration. Eleven programs (45.8%) provide either direct citizenship or access to PR. Southern European states in particular (Spain, Greece, and Portugal) have paired their DNV frameworks with permanent residency and naturalization opportunities, leveraging digital mobility to offset demographic decline and attract high-skilled labor. Northern and Western Europe (e.g., Germany, Netherlands, Norway, Italy, Ireland, Latvia) provide PR channels that typically lead to citizenship after 5–10 years of residence, consistent with EU naturalization standards.33 Importantly, EU citizenship multiplies the value of such pathways: once acquired, it grants full intra-EU mobility and settlement rights. Thus, for digital nomads, Europe represents not merely a residence option but a regional citizenship market, where DNVs can serve as entry points into one of the world’s strongest mobility regimes.

The Americas display a dual structure. In Latin America, five of nine states in the dataset (55.6%) (Brazil, Ecuador, El Salvador, Mexico, and Uruguay) allow PR conversion. These states are also notable for comparatively short naturalization timelines: in Ecuador and Uruguay, citizenship can be applied for after just 3 years of residence, far below Global North averages. This positions Latin America as a pragmatic route for digital nomads pursuing accelerated naturalization. Canada also fits this integrative model, permitting DNV holders to transition into its well-established permanent migration pathways.

By contrast, the Caribbean’s 11 jurisdictions overwhelmingly prohibit status conversion. DNVs in Antigua and Barbuda, Bahamas, Barbados, Dominica, Grenada, Saint Lucia, and othersfunction as lifestyle products aimed at high-income nomads, but without the political or legal integration of PR or citizenship.

The Asia-Pacific and Middle East stand out for their restrictive stance. None of the 10 Asian-Pacific jurisdictions in the dataset (Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, Malaysia, Sri Lanka, Thailand, India, Indonesia, Australia, Philippines) permit PR or citizenship conversion. The UAE, the region’s most prominent DNV provider, also denies pathways to permanent status. This reflects entrenched models of temporary labor migration in Asia and the Gulf, where governments capitalize on foreign labor without extending rights.32 In Africa, none of the five countries analyzed (South Africa, Mauritius, Seychelles, Namibia, Cabo Verde) tie DNVs to residency or citizenship. Despite these states’ growing appeal as affordable nomad destinations, the legal framework situates nomads firmly within short-term mobility regimes, with no route to political integration.

The divide between the Global North and Global South is sharp. In the dataset, 12 of 28 Global North jurisdictions (42.9%) provide PR or citizenship pathways, compared to just 5 of 36 Global South jurisdictions (13.9%), concentrated in Latin America. This disparity reflects broader global inequalities in passport strength. According to the Global Passport Index (2024), passports from the Global North routinely provide visa-free access to 150–190 destinations, while many Global South passports grant access to fewer than 100. Digital nomads from weaker-passport countries therefore face layered mobility restrictions: fewer DNVs available to them, shorter permitted stays, and little opportunity for transition to PR. Conversely, nomads from stronger-passport states can layer DNVs with existing mobility rights, creating what mobility portfolio where citizenship and residence rights are combined for maximum flexibility.

For digital nomads, acquiring a second citizenship can function as a strategic multiplier. In contexts where digital nomad visas are non-renewable, holding a stronger passport not only expands access to alternative programs but also reduces bureaucratic friction. In jurisdictions such as Spain, Portugal, Uruguay, or Ecuador (where naturalization timelines are comparatively short) citizenship or permanent residency becomes a viable mobility hedge. As Surak notes, “citizenship by acquisition is not only about entry rights, but about embedding oneself in more favorable global mobility regimes”.34 Similarly, Shachar underscores the rise of “strategic citizenship planning,” in which individuals accumulate multiple legal statuses to maximize economic and social opportunities.32 For digital nomads, who embody global labor mobility, second citizenship is thus more than symbolic: it is a practical tool to enhance resilience, expand travel freedoms, and secure long-term integration in stronger mobility regimes across the Global North and select Global South states.

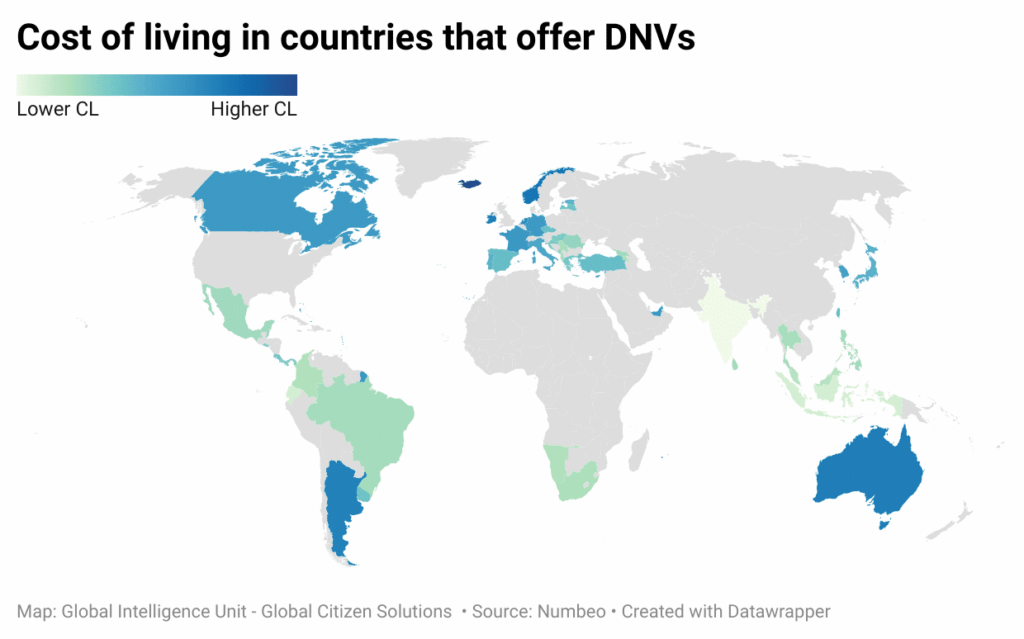

Economics

When comparing destinations, a global map of costs reveals three broad patterns that shape how digital nomads plan their stays. At one end are the “runway countries”, places where both living expenses and coworking fees remain accessible. Markets like India, Ecuador, Indonesia, Thailand and several in Eastern Europe and Southeast Asia fall into this category. In those countries, workspace rarely dominates a monthly budget, making these destinations attractive to freelancers, early-stage entrepreneurs, and anyone stretching savings while building a project. The combination of low overhead and a supportive nomad community helps explain why these countries so often serve as launchpads for longer stays.

In the middle sits a broad cluster where day-to-day costs are moderate and desk rentals fall into a manageable range. Much of Southern Europe and parts of Latin America belong to this band. They strike a balance: not the cheapest option, but also far from the premium rents seen further north. For many nomads, these regions offer an appealing blend of lifestyle, infrastructure, and affordability, making them particularly popular among those seeking to mix professional continuity with cultural immersion.

At the premium end are destinations where both living expenses and workspace rates run high. Northern Europe, Japan, and Australia exemplify this group, where strong infrastructure and innovation ecosystems come at a steep price. These markets tend to suit funded teams, corporate remote workers, or individuals who prioritize top-tier amenities over savings.

Beyond these broad categories, there are outliers worth noting. Some high-cost island economies combine expensive housing and groceries with relatively affordable coworking space, meaning the real challenge is everyday living rather than desk rental. Conversely, a few otherwise budget-friendly countries present disproportionately expensive workspace due to limited supply, reminding nomads to budget carefully at the city level rather than assuming national averages will hold.

Taken together, the picture is one of trade-offs. For digital nomads, the choice of destination is rarely just about the cheapest option. It is about how living costs, workspace access, and lifestyle intersect. Those seeking long-term sustainability may gravitate toward runway countries; those prioritizing cultural richness without breaking the bank often find balance in mid-cost hubs; and those with financial flexibility may opt for premium markets where infrastructure and professional ecosystems justify the higher outlay.

Tax Optimization

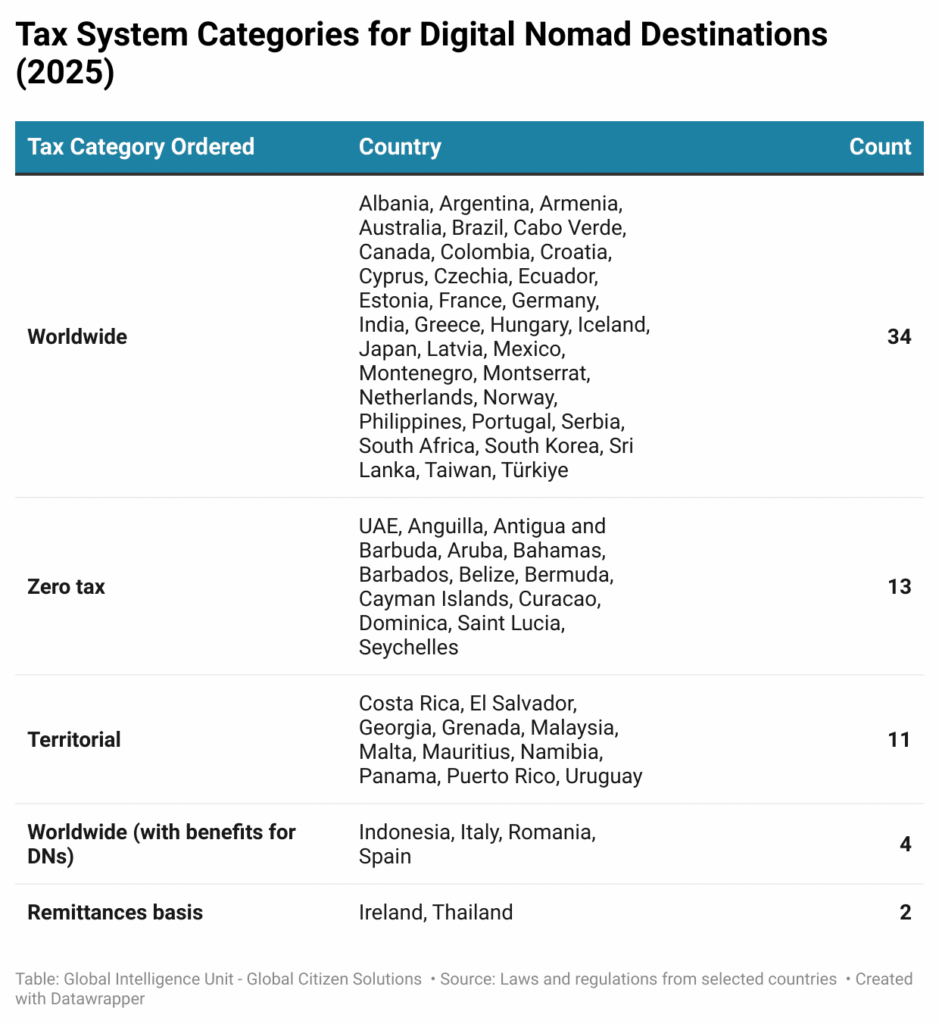

The rise of digital nomadism has pushed governments to reconsider how tax systems apply to globally mobile workers. Across 64 jurisdictions, five main tax categories emerge: worldwide taxation, zero-tax jurisdictions, territorial systems, remittance-basis systems, and a hybrid form of worldwide taxation with specific benefits for digital nomads. Each of these frameworks influences how individuals plan their financial affairs and how governments seek to attract talent and investment.

The distribution of tax regimes across 64 countries shows that worldwide taxation dominates at 53% (34 jurusdictions), underscoring how most states continue to apply traditional frameworks that tax residents on global income. Zero-tax systems 20% and territorial regimes 17% together make up over a third of the landscape, reflecting models often favored by mobile professionals seeking simplicity. Yet the chart bellow reveal how rare genuinely tailored concessions remain: only 6% of countries combine worldwide taxation with targeted benefits for digital nomads, while just 3% apply remittance-basis rules. Where exceptions do exist, they transform the picture: Spain’s Beckham Law allows newcomers to be taxed under a favorable expatriate regime for six years, Indonesia’s Omnibus Law temporarily limits taxation to local-source income for skilled foreigners, and Ireland’s remittance basis exempts foreign income not brought into the country. These measures illustrate how even countries with strict global taxation can design policies that attract talent without undermining fiscal sovereignty.

From a strategic policy perspective, the charts above highlight both competition and opportunity. With only a handful of states offering concessions, 6% under hybrid worldwide regimes with DN benefits and 3% under remittance systems, most governments risk treating digital nomads as tourists rather than long-term contributors. PwC notes that visa frameworks coupled with clear tax incentives can yield far more durable returns, including knowledge spillovers, entrepreneurial investment, and localized demand for services.35 Thailand’s 2024 reform, for example, ensures foreign income is taxed only if remitted, granting nomads greater planning flexibility, while Italy’s neo-domiciled regime offers significant relief for inbound professionals, as well as Spain’s Beckham Law. Together, these targeted rules show how fiscal design can shift digital nomadism from transient consumption toward sustainable integration. For policymakers, the implication is clear: the competitive edge will not come from visas alone but from coherent tax frameworks that balance attraction with compliance.

Additionally, Zero-tax and territorial systems appear especially attractive because they minimize or eliminate tax on foreign income, yet they are not as simple as they look. As Deloitte highlights, nomads may still trigger tax residency in their home country under day-count or ties tests, and their employers may face payroll or permanent establishment exposure if activities abroad are judged to constitute business operations.36 PwC similarly warns that territorial regimes must be analyzed in the context of double taxation treaties, since exemptions are often narrower than they appear. Worldwide systems, by contrast, tax global income and are often considered least favorable, but some of these jurisdictions have introduced targeted measures to offset the burden, recognizing that digital nomads bring skills and spending power.

Therefore, policy carve-outs are particularly important. Indonesia’s Omnibus Law allows foreigners who become tax residents to be taxed only on Indonesian-sourced income for their first four years if they meet certain skill requirements, effectively giving newcomers a territorial-style regime. Italy has created a favorable “neo-domiciled” regime, while Romania exempts salary income received from abroad when work is performed outside the country. Spain’s Beckham Law offers perhaps the best-known example, granting foreigners the option to be taxed under a favorable non-resident framework for six years. Ireland exempts foreign income not remitted into the country, and Thailand has reformed its tax system so that, starting in 2024, only remitted foreign income is taxed.

These dynamics show why exceptions often matter more than the broad categories themselves. A worldwide jurisdiction with a generous expatriate program can be more appealing than a territorial system with no relief. Remittance-basis systems provide timing flexibility, while temporary exemptions such as Indonesia’s four-year rule or Spain’s six-year Beckham Law give nomads a planning window to settle or diversify. PwC emphasizes that governments using digital nomad visas as economic development tools must integrate them with labor, tax, and investment frameworks, rather than leaving them as short-term tourism substitutes.35

For states, the task is to move beyond pandemic-era “minimum viable” visas and design sustainable tax frameworks that integrate nomads into their economies. Properly structured, digital nomadism is not just a lifestyle trend but a potential channel for foreign direct investment, entrepreneurship, and human capital inflows.

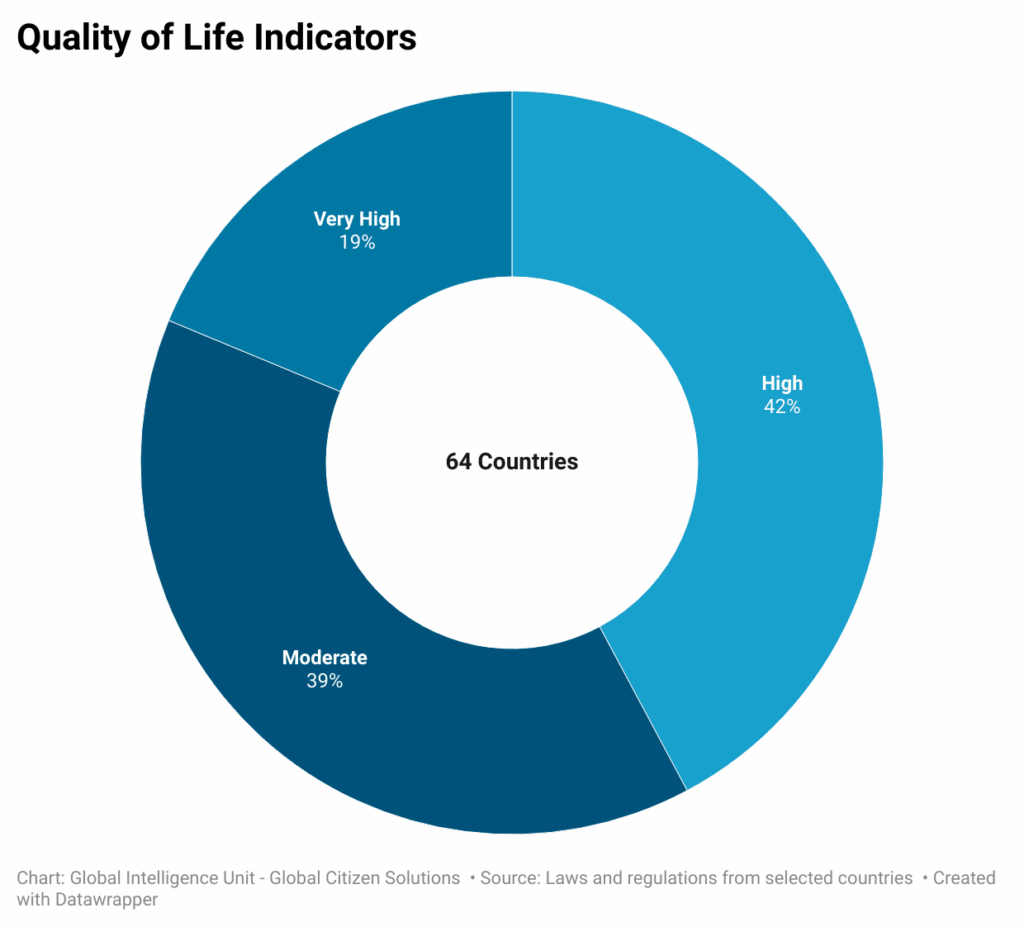

Quality of Life

Quality of life is one of the strongest drivers for digital nomads when deciding where to live and work. While tax incentives, visa duration, and internet infrastructure are important, nomads ultimately choose destinations that offer safety, comfort, healthcare, and cultural vibrancy. Even in places where overall national indicators are modest, nomads often create communities that foster a safe and fulfilling lifestyle. This makes quality of life not just a statistic, but a lived experience that shapes global mobility choices.

As it carries an inherently subjective dimension, for many DNs, the appeal of a destination is shaped not only by measurable indicators but also by personal preferences, such as climate, cultural environment, and the alignment of local values with one’s own lifestyle. While these aspects cannot be fully quantified, they are central to the decision-making process of individuals who prioritize both professional opportunities and personal fulfillment in their choice of where to live and work.

To provide a structured, data-driven perspective, the Global Digital Nomad Report applies the Global Citizen Solutions Passport Index metrics as the basis for evaluating quality of life. This ensures consistency, comparability, and methodological rigor, while also recognizing that lived experiences may differ from aggregated data.

The Quality of Life Index measures the overall living standards a country offers, emphasizing features that make destinations attractive for retirees, expats, digital nomads, and globally mobile individuals seeking favorable living conditions. Research prioritized reliable sources with comprehensive country coverage, leading to the inclusion of six weighted indicators:

- Sustainable Development Goals (30%) – Progress toward UN development benchmarks reflecting health, education, equality, and sustainability.

- Cost of Living (20%) – Affordability of essential goods and services, housing, and daily expenses.

- Freedom in the World (20%) – Political rights and civil liberties, capturing openness and democratic governance.

- Happiness Score (10%) – Subjective well-being and life satisfaction as measured by the World Happiness Report.

- Environmental Performance (10%) – National efforts in sustainability, pollution control, and natural resource protection.

- Migrant Acceptance (10%) – Public attitudes toward migration, signaling how welcoming societies are to foreigners.

Together, these indicators form a balanced and comprehensive framework for assessing the quality of life across destinations, providing both policymakers and digital nomads with a transparent, comparative tool to guide decisions.

Out of the 64 countries analyzed, the largest share (27 countries, or 42.2%) fall into the High quality of life category. An additional 12 countries (18.8%) rank Very High, together making up more than 60% (61.0%) of all destinations. This group includes world-class locations like Germany, Norway, the Netherlands, Spain, Canada, and Uruguay, where digital nomads can expect excellent living standards. Another 25 countries (39.0%) rank Moderate, offering comfortable but less comprehensive conditions.

Europe and Oceania

Europe clearly dominates the High and Very High groups, with more than half of its participating countries offering some of the best living conditions worldwide. Nations such as Germany, Norway, the Netherlands, and Spain occupy the Very High tier, while Portugal, Italy, Greece, France, and Czechia rank High, making Europe the strongest regional hub for digital nomads seeking premium standards. Eastern European states like Romania, Latvia, and Croatia also offer a high quality of life, providing lower costs but still relatively strong social safety nets and infrastructure compared to other regions.

Australia ranks in the very high quality of life category, reflecting its excellent healthcare, safety, and urban infrastructure. Cities like Sydney, Melbourne, and Brisbane consistently score among the best in the world for livability, offering clean environments, cultural vibrancy, and strong work-life balance. For digital nomads, Australia combines a reliable internet infrastructure with a cosmopolitan lifestyle and easy access to beaches, nature, and outdoor activities. While the cost of living is high, the overall standard of living remains one of the most attractive globally, making Australia a strong choice for nomads seeking both professional stability and lifestyle enrichment.

Americas & Islands

In the Americas, Canada and Uruguay are standouts in the Very High tier, offering stability, safety, and infrastructure. Latin American countries such as Brazil, Mexico, Colombia, and Ecuador tend to sit in the High or Moderate categories, balancing affordability with improving services. In the Caribbean and small island states, most countries (including Cayman Islands, Bahamas, Barbados, and Dominica) rank High, showing that even lifestyle-oriented destinations with limited infrastructure are able to provide a quality of life appealing to nomads.

In Africa, digital nomad destinations generally fall into the Moderate quality of life tier, with a few notable exceptions. South Africa and Mauritius stand out in the High category, offering strong infrastructure, vibrant urban centers, and established expatriate communities that appeal to long-term remote workers. Other countries such as Namibia and Cabo Verde tend to be classified as Moderate, where natural beauty and lifestyle appeal often outweigh gaps in infrastructure or public services. Overall, while Africa does not dominate the global rankings, it provides attractive options for nomads seeking affordability, cultural diversity, and unique environments, particularly in coastal hubs and well-connected cities.

Technology and Innovation

While cost of living, visa accessibility, and lifestyle remain important, reliable internet speed and an innovation-driven environment often act as decisive factors. For nomads working in tech, finance, creative industries, and remote services, a country’s ability to guarantee high-quality digital infrastructure and foster innovative ecosystems can determine its attractiveness as a long-term base.

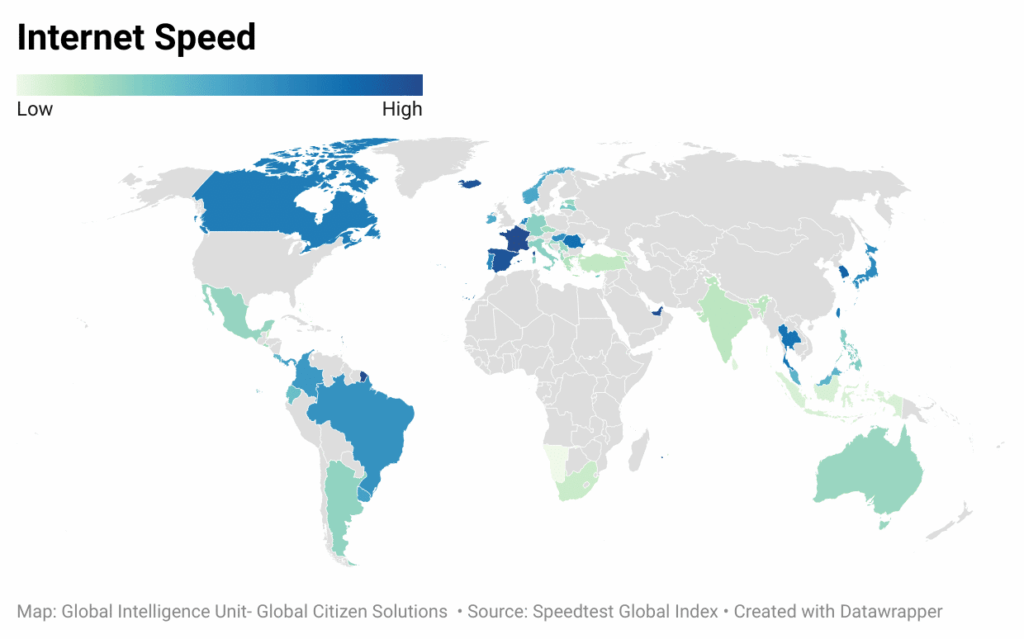

Globally, digital nomad destinations show a mixed performance in internet connectivity. Based on the latest data, only about 12.5% of countries offer very high internet speeds (above 150 Mbps), concentrated in advanced economies such as Germany, Spain, South Korea, Taiwan, Iceland, and Canada. A broader group, about 58%, sits in the moderate-to-high range (50–150 Mbps), sufficient for remote work but with occasional limitations for bandwidth-intensive tasks. However, nearly one-third (29.7%) of countries remain in the low-speed category, including popular lifestyle hubs in the Caribbean and parts of Latin America and Africa, where infrastructure lags behind rising demand. For digital nomads, slow or unstable internet is a dealbreaker, making these destinations less competitive despite other lifestyle advantages.

Alongside speed, innovation ecosystems play a crucial role. Countries ranked high on global innovation indexes (such as South Korea, Germany, France, the Netherlands, and Taiwan) attract nomads not only for connectivity but also for professional opportunities, networking, and knowledge spillovers. In contrast, destinations offering only lifestyle advantages without fostering innovation risk becoming transient stopovers rather than hubs for long-term digital migration. Innovation matters because nomads often seek integration into ecosystems that provide co-working spaces, digital services, start-up networks, and access to skilled communities.

To remain competitive, countries must invest strategically in both connectivity and innovation. Expanding fiber-optic coverage, ensuring affordable high-speed mobile data, and improving service reliability are foundational steps. Equally, governments can incentivize innovation through support for start-ups, streamlined regulations, and partnerships with global tech firms. Small and emerging economies, especially in the Caribbean, Africa, and parts of Asia, could leverage their natural and cultural appeal while addressing infrastructure bottlenecks to create well-rounded offers for digital nomads. In short, beyond beaches and visas, what truly keeps nomads is fast internet and thriving innovation ecosystems.

Over the past two decades, digital nomadism has transformed from a niche subculture into a global movement, with millions of professionals seeking geographic flexibility, cultural immersion, and improved quality of life. This shift has prompted governments to formalize pathways for long-term remote workers through digital nomad visas, which allow foreigners to reside and work remotely from their territories without competing directly in the local labor market.

Digital-nomad visas have matured from pandemic experiments into a deliberate talent-and-investment policy. In our current Top 10, Europe accounts for about 70% of winners (Spain, Netherlands, Czechia, Portugal, France, Germany, Malta), the Americas contribute 20% (Canada, Uruguay), and the Middle East/Asia the remaining 10% (UAE). That distribution reflects a simple logic: places that combine clean rules with regional mobility, dependable infrastructure, and day-to-day affordability turn mobile professionals into year-round contributors rather than transient visitors.

The 2025 Global Digital Nomad Report analysed 64 jurisdictions and the top 10 destinations for digital nomads in 2025 are:

1st – Spain

Spain’s Startup Law (Law 28/2022)37 formalized an “international teleworking” route that lets third-country professionals reside in Spain to work remotely, and (crucially for freelancers) earn up to 20% of their revenue from Spanish clients while keeping the bulk of their portfolio abroad, a small design that meaningfully eases local integration into hubs, suppliers, and coworking ecosystems. The same law broadened and extended Spain’s impatriate (“Beckham”) tax regime to six years38, which many newcomers use to plan costs in their first phase on the ground. Spain pairs these rules with world-class connectivity (fixed broadband speeds consistently among Europe’s fastest) and a robust, mid-pack innovation profile that still benefits from EU-wide programs and clusters.

Additionally, Spain stands out as a premier destination for digital nomads, ranking among the top 10 in the Quality of Life Index but also offering one of the most favorable legal frameworks for long-term integration. Under its digital nomad visa, Spain provides a direct pathway to citizenship, and for nationals of Ibero-American countries, the Philippines, and Equatorial Guinea, the naturalization period is shortened to just two years, compared to the standard ten. From an economic perspective, Spain is more affordable than many Northern European countries, particularly in secondary cities, where the cost of living is lower while maintaining high standards of safety, healthcare, and amenities. Reliable and inexpensive public transportation connects even smaller urban centers, and fast, widespread internet access ensures that digital nomads can work efficiently from virtually anywhere. These advantages mean that Spain is well-positioned to encourage geographic diversification of relocation, spreading the benefits of nomad inflows beyond Madrid and Barcelona to medium-sized and regional cities, thereby supporting balanced development.

2nd – The Netherlands

Rather than a classic digital-nomad visa, the Netherlands channels remote professionals through well-trodden pathways: the IND’s self-employed permit (assessed on “essential interest” to the Dutch economy via an RVO points system) and the Start-up route with an approved facilitator, both of which allow you to base in a highly reliable business environment while serving foreign clients.39

The Netherlands ranks second globally in the Global Digital Nomad Index, reflecting its balanced performance across the six thematic sub-indices. While its Procedure Index position (13th) shows that entry requirements are relatively structured compared to some jurisdictions, the Dutch framework excels in long-term opportunities: the Citizenship and Mobility Index ranks 4th, since the self-employed residence permit provides access to permanent residency, placing the country among Europe’s most integration-friendly destinations. On Tax Optimisation, the Netherlands is less competitive (28th), as it applies a worldwide tax regime, but this is offset by its exceptional performance in Quality of Life (1st), with top-tier healthcare, safety, cultural amenities, and urban livability. The Tech and Innovation Index (7th) further underlines the country’s role as a European innovation hub, with fast internet, strong research ecosystems, and a thriving startup scene. Economically, the Netherlands ranks 49th, reflecting higher costs of living, but its reliability, connectivity, and long-term stability make it one of the most attractive digital nomad destinations in the world. By excelling in Quality of Life and Mobility, while leveraging its innovation ecosystem, the Netherlands demonstrates how a well-rounded policy framework can transform into global leadership in digital nomadism.

Add to that the world’s top English proficiency (EF EPI) and a perennial top-10 innovation ranking, and the country’s proposition becomes clear: predictable administration, dense client markets, and a deep tech ecosystem in exchange for higher day-to-day costs.

3rd – Uruguay

Uruguay has leaned into simplicity and safety to position itself as a Southern Cone base: a decree-backed digital-nomad stay/residence path that can be initiated online and streamlined follow-on residence options, all in a country that consistently ranks among the most peaceful in the Americas on the Global Peace Index. While its innovation rank trails OECD leaders, Montevideo’s stability, strong public services, and low-friction government portals are exactly what many nomads and founders want when formalizing a Latin American footprint.

Uruguay ranks third worldwide in the Global Digital Nomad Index, standing out as a leading destination in the Americas thanks to its balanced performance across the six sub-indices. Its Citizenship and Mobility Index (5th) highlights Uruguay’s openness, as the provisional identity card granted to digital nomads allows access to permanent residency and, uniquely, a relatively short path to citizenship after five years of residence.40 In Economics (29th), Uruguay offers a moderate cost of living compared to Northern countries, while maintaining stability and access to affordable services. Its Tax Optimisation Index (15th) reflects the territorial system, which exempts foreign-sourced income from taxation unless remitted, a key incentive for mobile professionals. The country also performs strongly in Tech & Innovation(19th), with solid digital infrastructure and reliable internet, and its Quality of Life Index (24th) underscores safety, democratic stability, and a vibrant cultural environment. Uruguay’s Procedure Index (17th) shows efficient regulation, as applications can be processed smoothly and extended, providing continuity for long-term stays. Overall, Uruguay combines affordability, residency opportunities, and democratic stability, making it one of the most strategic relocation choices for digital nomads in Latin America.

4th – Canada

Canada ranks fourth in the Global Digital Nomad Index, reflecting its strong position as one of the most attractive destinations for remote professionals. The country excels in the Procedure Index (5th), offering a clear and straightforward framework for digital nomads through its visitor visa, eTA, and temporary resident visa pathways, all of which are extendable. In terms of Citizenship and Mobility (5th), Canada stands out for granting access to permanent residency, which can eventually lead to citizenship under its well-established immigration system.41 Its Tech & Innovation Index (8th) is another highlight, thanks to widespread high-speed internet, cutting-edge research institutions, and dynamic startup ecosystems. The Quality of Life Index (12th) underscores Canada’s appeal, with very high living standards, excellent healthcare, and cosmopolitan cities like Toronto, Vancouver, and Montreal. Although the Economics Index(44th) shows that Canada is a relatively high-cost destination, especially in urban centers, its Tax Optimisation Index(29th) and policy clarity mitigate risks for nomads. Overall, Canada offers a unique combination of long-term migration opportunities, innovation ecosystems, and high quality of life, making it a premier destination for digital nomads seeking stability and integration in the Global North.

5th – Czechia

Czechia ranks fifth in the Global Digital Nomad Index, emerging as one of the strongest hubs in Central Europe for remote professionals. It performs exceptionally well in the Citizenship and Mobility Index (2nd), as it is one of the very few countries offering a direct pathway to citizenship through its digital nomad visa framework, particularly for nationals of select partner countries. Its Procedure Index (40th) is less competitive due to stricter eligibility requirements, such as limiting applications to nationals from countries including the US, UK, Canada, Japan, South Korea, and several others—but once admitted, nomads benefit from a renewable 1-year visa. In the Quality of Life Index (10th), Czechia offers high living standards, a safe environment, and vibrant cultural cities like Prague and Brno, combined with relatively moderate living costs compared to Western Europe. The Economics Index (31st) and Tax Optimisation Index(30th) place Czechia in a balanced position: not the cheapest option, but affordable and competitive for long-term settlement. Finally, while its Tech & Innovation Index (32nd) is mid-tier, the country provides solid digital infrastructure and a growing startup ecosystem. Overall, Czechia’s mix of direct citizenship opportunities, cultural richness, and affordability positions it as a strategic choice for digital nomads looking for long-term integration within the European Union.

6th – Portugal

Portugal’s D8 “remote worker” residence route gives nomads either a temporary-stay visa or a residence permit (the latter typically valid for two years, renewable). The country couples that with excellent fiber and mobile speeds and an innovation profile that—while mid-table—benefits from an outsized start-up scene and strong EU research links; for many solo operators and small teams, that mix of reliability, lifestyle, and EU mobility is the draw.

Portugal ranks sixth in the Global Digital Nomad Index, standing out as one of Europe’s most attractive destinations for mobile professionals. Under its D8 Visa, created in 2022, Portugal allows third-country nationals to apply remotely for a renewable one-year residence permit, with a clear pathway to permanent residency and eventually citizenship. This makes Portugal highly competitive in the Citizenship and Mobility Index (4th), as long-term settlement is not only possible but legally structured. In the Procedure Index (27th), Portugal benefits from a relatively straightforward process, though income thresholds and documentation requirements remain moderately demanding. On the Quality of Life Index(14th), the country offers an excellent lifestyle: vibrant cities like Lisbon and Porto, reliable public transport, affordable healthcare, and a Mediterranean climate that makes it especially attractive to nomads. The Economics Index (35th) reflects its moderate cost of living, which is cheaper than in most Northern European countries, especially in secondary cities and inland regions, where relocation can be encouraged. While Portugal’s Tax Optimisation Index (31st) reflects its worldwide taxation, the country has historically offered favorable regimes such as the Non-Habitual Resident (NHR) program, which, despite reforms, continues to provide tax incentives for foreign professionals from specific professional backgrounds. Finally, in the Tech & Innovation Index (12th), Portugal benefits from its growing startup ecosystem, international connectivity, and high internet speed. Altogether, Portugal offers a balanced and strategic package, making it one of the top choices for digital nomads seeking both lifestyle quality and long-term integration in Europe.

7th – France

France ranks 7th in the Global Digital Nomad Index, reflecting its strong performance across several dimensions that matter most to mobile professionals. The country operates its Long-Stay Visa (VLS-TS), launched in 2019, which grants a renewable one-year stay for non-EU/EEA/Swiss nationals. While France does not provide a direct pathway to citizenship under its digital nomad framework, it remains highly competitive in the Citizenship and Mobility Index(6th) thanks to broader French and EU residency frameworks that nomads can later access.

On the Quality of Life Index (15th), France offers an enviable lifestyle, combining world-class healthcare, cultural richness, and excellent infrastructure. Internet speed is very high, and its cities consistently rank among the world’s most livable. France also tops the Tech & Innovation Index (1st), reflecting its global leadership in R&D, startup ecosystems, and higher education, which provides fertile ground for networking and collaboration. In the Economics Index (47th), costs of living are relatively high (particularly in Paris) but secondary cities like Lyon, Bordeaux, and Nantes provide more affordable alternatives with excellent transport connectivity.

Taxation remains a challenge, with France falling to 32nd in the Tax Optimisation Index due to its worldwide taxation regime and relatively high marginal rates. However, this is offset by strong public services, robust worker protections, and a vibrant entrepreneurial ecosystem that attracts talent. Overall, France balances high living standards with innovation leadership, making it a prime destination for digital nomads who value infrastructure, culture, and professional opportunities, even if costs and taxes are steeper than in competing jurisdictions.

8th – Germany

Germany ranks 9th in the Global Digital Nomad Index, standing out as one of Europe’s most attractive destinations for remote professionals seeking stability, infrastructure, and long-term integration. Its Freelance Visa (Freiberufler), introduced in 2021, allows stays of up to three years, one of the longest durations among digital nomad visa frameworks. While the visa is not renewable, Germany offers access to permanent residency after five years, which can ultimately lead to citizenship, making it highly competitive in the Citizenship and Mobility Index (4th).

Germany also excels in the Quality of Life Index (5th), offering world-class healthcare, education, and public services alongside vibrant cultural hubs in cities like Berlin, Munich, and Hamburg. Internet speed is moderate, but widespread coverage ensures reliable connectivity across most regions. In the Tech & Innovation Index (22nd), Germany leverages its strong industrial base, robust R&D investment, and thriving startup ecosystem, particularly in fintech, AI, and green technologies, to create opportunities for digital entrepreneurs and skilled professionals alike.

On the Economics Index (45th), Germany is less competitive due to relatively high living costs, particularly in major cities, though smaller towns and secondary urban areas offer more affordable options. Taxation remains one of its key drawbacks, with the country ranking 33rd in the Tax Optimisation Index under a worldwide taxation system that imposes some of the highest marginal rates in Europe.

Despite these financial hurdles, Germany’s combination of long visa duration, access to permanent residency, high quality of life, and innovation-friendly environment makes it a strategic choice for digital nomads seeking not just a temporary base, but a pathway to long-term settlement in one of Europe’s strongest economies.

9th – United Arab Emirates

The UAE designed a nomad-friendly offer around speed and tax clarity: Dubai’s and Abu Dhabi’s remote-work visas let foreign professionals base in a hyper-connected hub for up to a year (renewable), while the federal tax framework imposes no personal income tax on salaries and applies corporate tax only to business profits above threshold; applicants should always check the latest salary/insurance requirements with the issuing authority.

The United Arab Emirates (UAE) ranks 8th in the Global Digital Nomad Index, standing out as one of the most attractive destinations in the Middle East for remote professionals. Its Remote Work Visa, launched in 2021, allows foreigners to live and work in the UAE for up to one year, with the possibility of renewal. However, unlike many European counterparts, the UAE does not provide a pathway to permanent residency or citizenship, positioning it firmly as a short- to medium-term hub rather than a long-term settlement destination.

Where the UAE truly excels is in the Tax Optimisation Index, where it ranks 1st globally. As a zero-tax jurisdiction, it eliminates income tax burdens entirely, making it particularly attractive for high-earning digital nomads and entrepreneurs. This, combined with the country’s 11th place in Quality of Life and 3rd place in Tech & Innovation, underscores the UAE’s reputation as a premium global hub. Cities like Dubai and Abu Dhabi offer world-class infrastructure, efficient public services, and highly reliable high-speed internet, placing them among the most connected urban environments worldwide.

Economically, the UAE balances its 46th place in the Economics Index with an expensive but high-quality lifestyle. While the cost of living is high, nomads benefit from the country’s cosmopolitan environment, excellent transport links, and an ecosystem designed to attract global talent, from free zones to startup incubators. Its moderate English proficiency still allows easy communication in professional and social settings, given English’s dominance in business and expatriate life.

In sum, the UAE represents one of the best short-term destinations for digital nomads, particularly those who prioritize tax efficiency, connectivity, and lifestyle quality. While its lack of long-term migration pathways limits integration, its global air links, innovation ecosystem, and tax advantages secure its place as a strategic base for internationally mobile professionals.

10th – Malta